‘XVI. Bringing Down the House of God.’ edited by Peter Grey and Alkistis Dimech

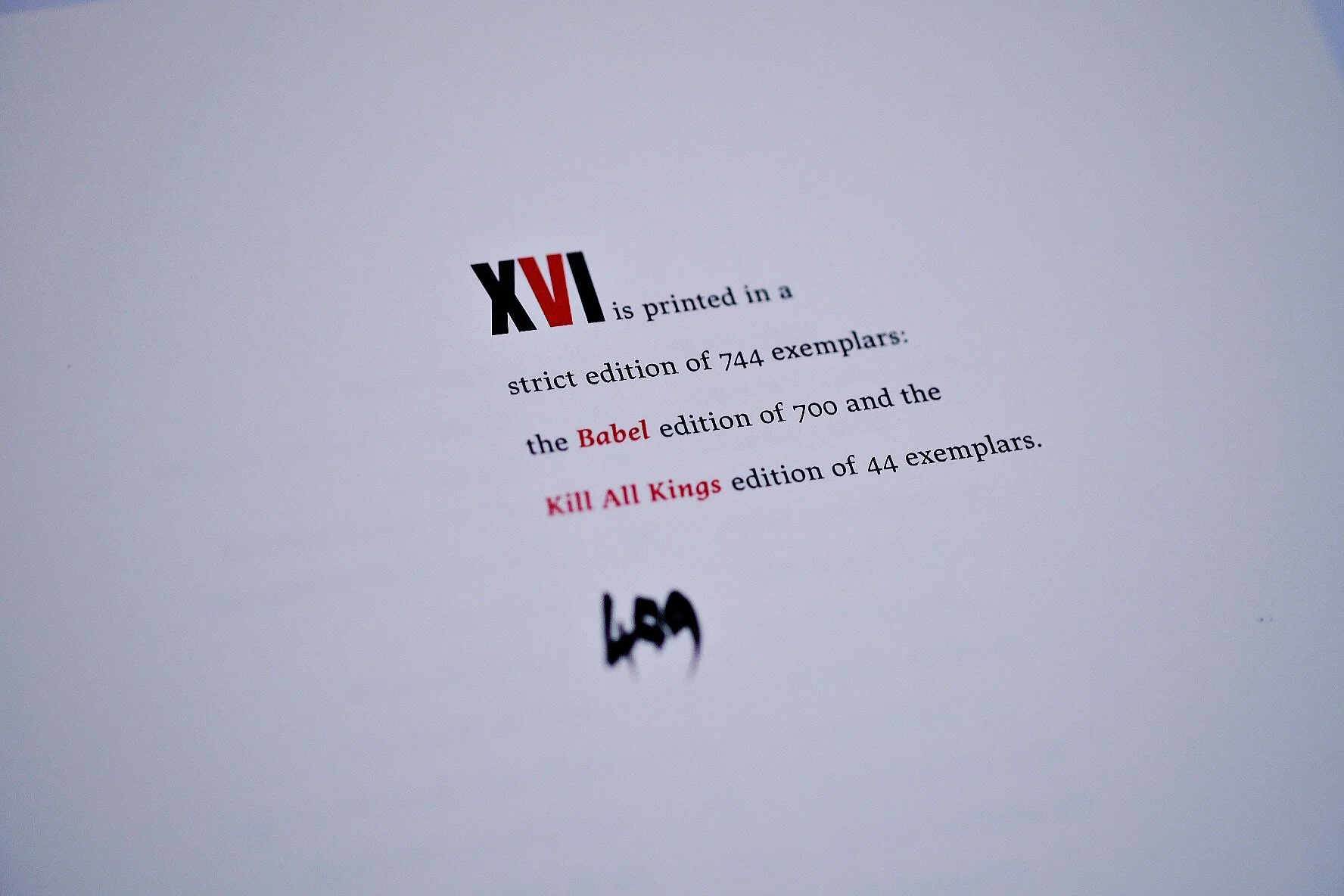

Review: XVI. Bringing Down the House of God. Edited by Peter Grey & Alkestis Dimech. London: Scarlet Imprint, 2010, "The Babel Edition" hardcover, large octavo, 280pp

We live in the time of radical change, anxiously poised between hopes of scientifically secured future characterized by disease-less abundance on one hand, and the fears of ecological and economic collapse on the other. Significant contributors to the current political unrest are increasingly opposed religious ideologies, in particular those of the Abrahamic monotheisms, with their mutually exclusive and potentially destructive agendas. As is to be expected, representatives of esoteric currents are to a varying degree similarly involved in the debate about contemporary political and social issues. On the subject of speculative history, one of the dominant discourses among esotericists concerns humanity’s supposed entrance into the new age, often glossed under the rubric of the Age of Aquarius, more recently focused on the hypothetical Mayan calendar’s prediction of fundamental global change that is to occur in 2012, but arguably most influentially in light of Aleister Crowley’s teaching about the advent of the New Aeon of the Child Horus marked by the new dispensation annunciated by the prophetic text of The Book of the Law and its doctrine of Thelema. In his numerous writings, Crowley proposed that the transition from the previous Aeon of Osiris characterized by the reign of patriarchy into the New Aeon is going to be volatile and that it may involve the catastrophic breakup of the old civilization. It is thus possible to adopt this ideological perspective as a working interpretative model and to view the current global situation in light of the collapse of the symbolical order marked by the reign of the Father – or, as Lacan would say, the Name of the Father – and to interrogate the conceptual resonance of this situation with the emergence of the New Aeon.

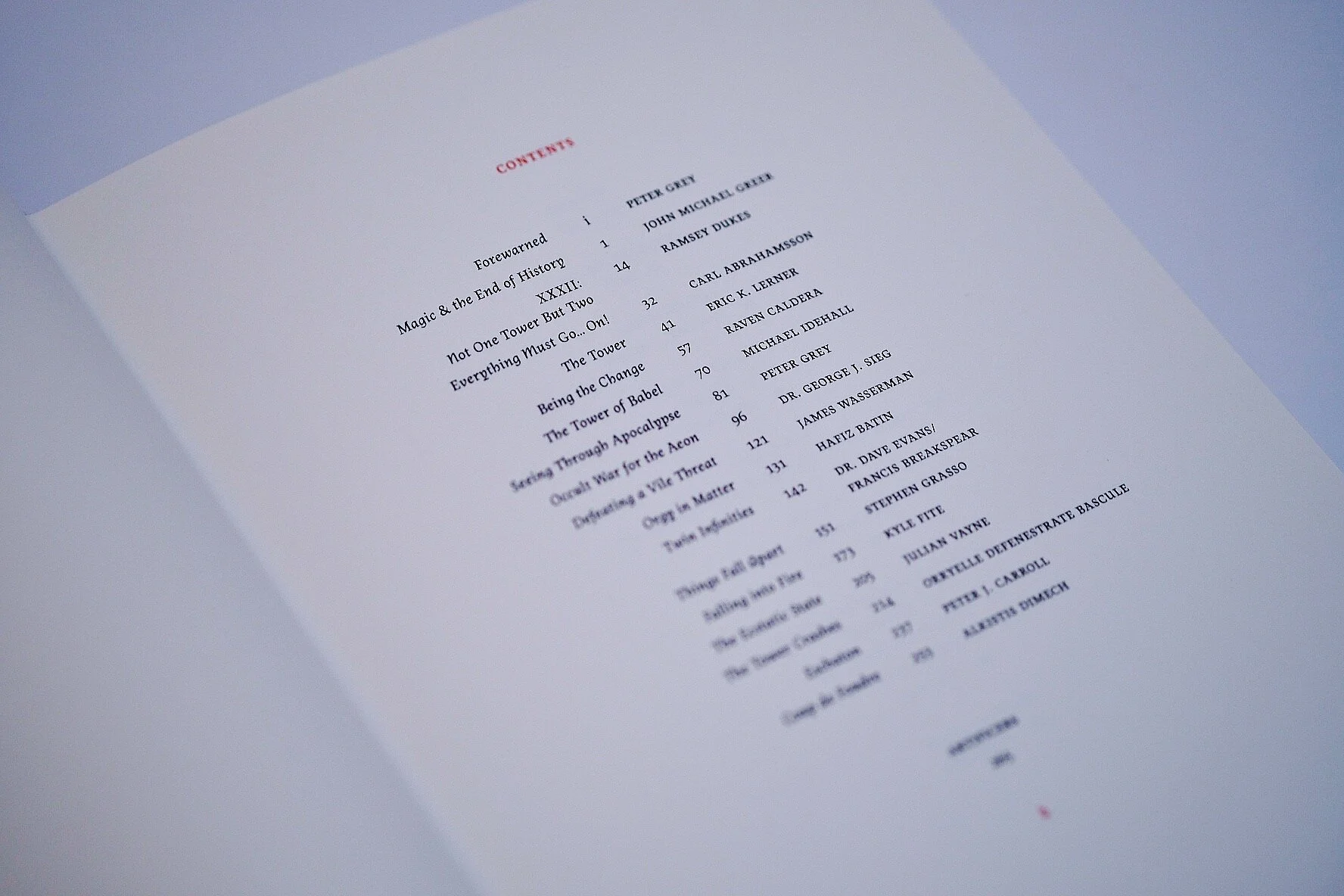

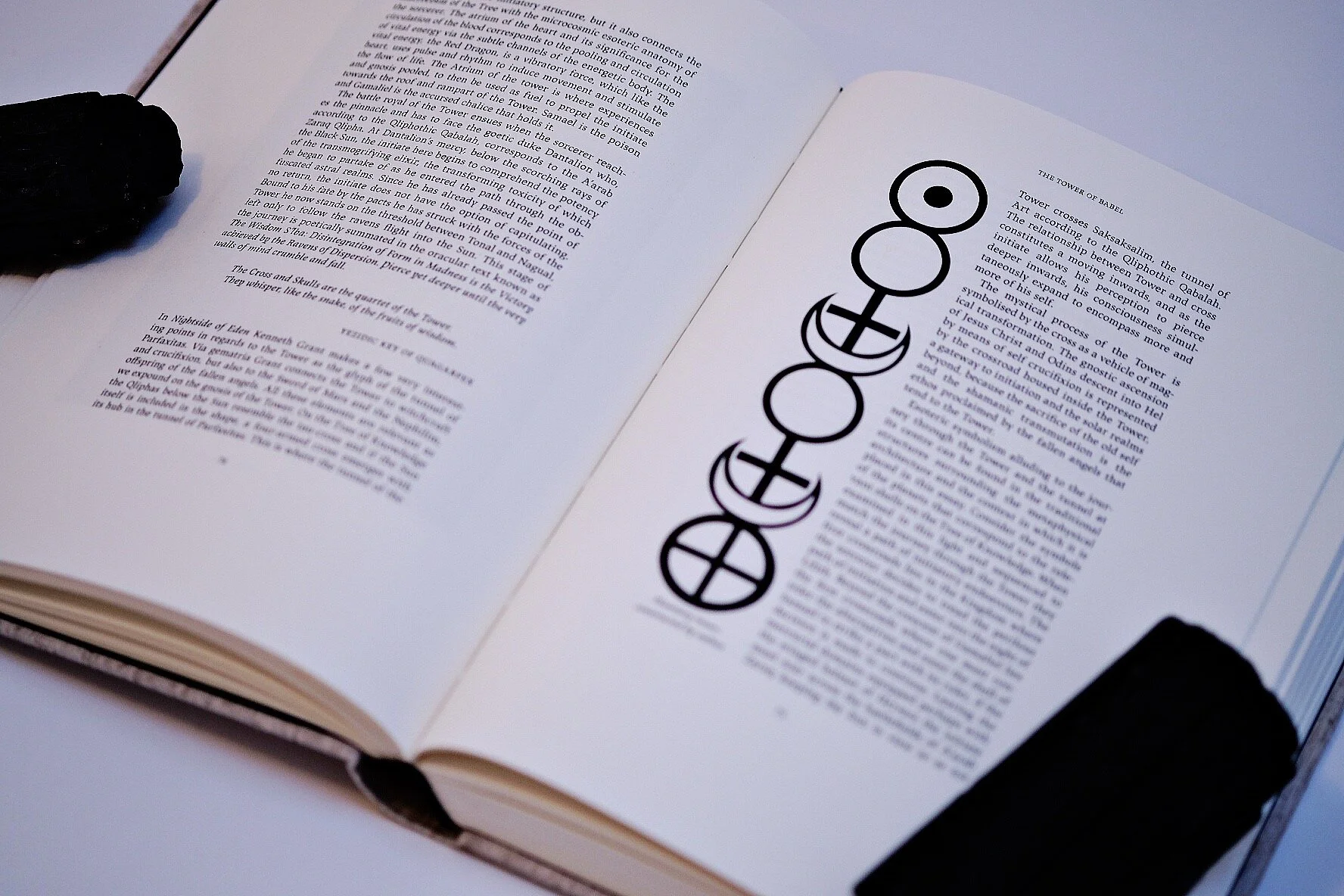

A recent collection of distinctly apocalyptic essays gathered under the title XVI, which refers to the number of the Tarot Card otherwise known as “The Tower” or “The House of God” is permeated by the ideological universe described above. The conceptual focus of the collection consists of the image of the blasted Tower and the individual authors’ essays interpret the meaning of its fall. Sixteen authors muse on the meaning of the card, taking it as the point of departure in order to discuss the perceived collapse of our present civilization, the ecological and economic crisis, and magical ways of coping with the end of the “age of exuberance,” the breakdown of authority, and the initiatic experience of the dissolution of one’s own sense of separate identity: the collapse of the Reign of the Father, seen under the sign of the Falling Tower. As Peter Grey, co-editor of the volume (and co-owner of the Scarlet Imprint publishing company) writes in his introductory essay:

The symbol of our civilisation is the city, and the symbol of the city is the tower. Seven steps to divinity which began in Sumeria. But the tower is seen as malefic, under the influence of Mars. A setting above the ignorant masses, the few celebrating penthouse consummations with paid for priestesses, sheer sided watchtowers rising above the prison. Perhaps it has always been so, but this is the age in which the Tower has reached its apotheosis (“Forewarned,” p. i).

Essays in the collection address an array of contemporary crisis situations and calamities and correlate their impact and meaning with the symbol of the fallen Tower. The opinions are diverse and the views often verge on disturbing: there is certainly nothing in the book that would be acceptable to everyone, and that is as it should be. The overall message is however clear: it’s the end of the world as we know it, whether we like it or not. “If there is one piece of alchemical arithmetic you need to take away from this entire book, it is this: for every one calorie of food produced, ten calories of oil are needed to produce it” (Peter Grey, “Seeing Through Apocalypse,” p. 92; emphasis in the original). You do the math.

It would be inaccurate, however, to think that this is a volume of gloom. Quite the opposite, the bulk of the essays urge towards action: magical, political, ecological, erotic, you name it. To quote Grey again, “In opposition to the Tower we raise the image of the maypole. A living symbol on a human scale. An image of resistance” (“Forewarned,” p. iii). In a similar vein, Peter Carroll suggests the following as a vision of an alternative state of affairs: “Imagine a society where neighbourhoods had their own magical temples where people could come to learn and practice meditation, visualization, trance, ritual, invocation, enchantment and divination, free from theological dogma, purely as mental techniques” (“Eschaton,” p. 250).

The authors are for the most part actively engaged in one or several aspects of esoteric theory and practice, and are affiliated with movements and magical orders such as Nordic Shamanism, Chaos Magick, the Typhonian Order, Santería, Voudon, the Illuminates of Thanateros, Ordo Templi Orientis, and the like. As already indicated, there is a very strong apocalyptic undercurrent behind a good deal of the writing, but the general trend of the collection is aimed at providing a vision of possible magical and mystical ways of coping with the situation at hand. This is neatly illustrated by Carroll who telescopes the issue into two questions:

A: Can the pursuit of Magic offer an attractive alternative to religion and the political-economic religion of consumerism?

B: Would the widespread adoption of the pursuit of Magic reduce humanity’s current suicidal reliance on religion and excessive consumption? (“Eschaton,” p. 246.)

The questions remain even more relevant now than they were a decade ago when the book was originally published. And the effort to provide satisfactory answers continues, with an ever-increasing sense of urgency.

On a more technical note, the book is a beautifully produced hard-cover volume graced by the black-and white rendition of “The Tower,” executed by Kyle Fite.

Highly recommended. But be forewarned: “By the mere possession of this book, you too are implicated” (Grey, “Forewarned,” p. iii).