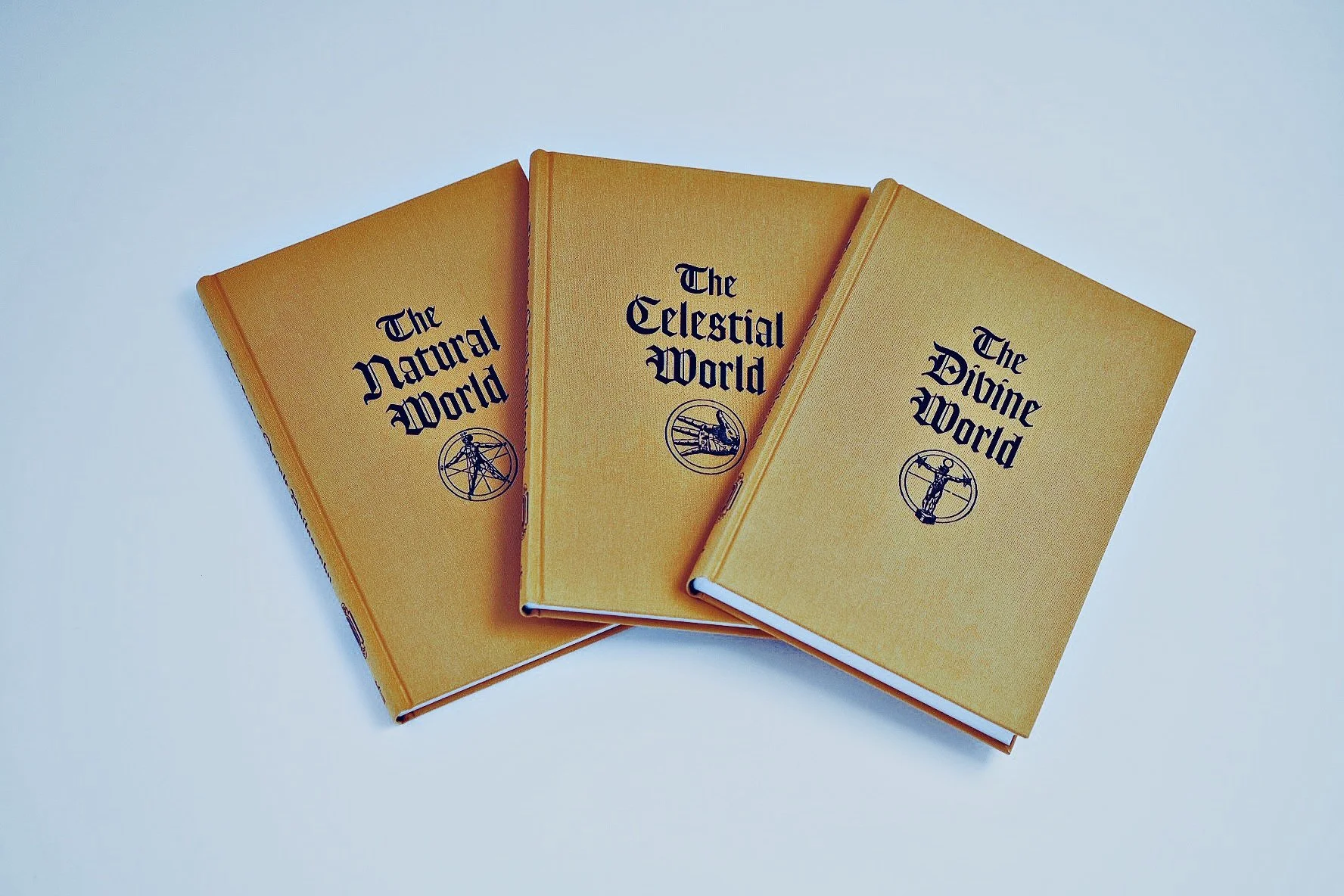

‘Three Books of Occult Philosophy’, Translated by Eric Purdue

Review: Henry Cornelius Agrippa, Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Translated by Eric Purdue, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2021, ISBN 978-1-64411-416-2

Gains and Disputes in Translation:

Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy

In the publisher’s preface to this latest English Translation of Agrippa’s Three Books Ehud Sperling suggests that

Occult Philosophy is the antidote to what a contemporary poet called “The War on the Imagination.” (Purdue, Three Books, xviii)

This poet, we need to acknowledge, was none other than Diane DiPrima who in fact taught herself medieval Latin in order to better access the works of John Dee as well as other magicians and alchemists of the mid-ages. DiPrima’s devotion to the distribution of Latinate esoteric texts beginning in the 1950’s was considerable. Her zeal was in part due to the dearth of these works in translation that set her on this course in conjunction with her endeavors as a poet and magician. For DiPrima, as well as Agrippa, these two pursuits were part and parcel of a unified front.

To be precise, DiPrima, in her poem, “Rant” proclaimed:

THE ONLY WAR THAT MATTERS IS THE WAR AGAINST THE IMAGINATION

ALL OTHER WARS ARE SUBSUMED IN IT[1]

As she stated prior to this declaration, “nothing adds up and nothing stands in for anything else.”[2] The significance of the act of translation then, within this light, should be reckoned and wrestled with as both contributing to yet always acting against the grain of the original work. The presence of this fundamental tension that is inherent in all translations should never be overlooked. And as we shall see, this sort of conflict is worthy of additional consideration as one works through this most recent translation of Agrippa’s Three Books.

In his recent rendition of the Three Books, Eric Purdue has consulted Vittoria Perrone Compagni’s critical edition, which is based primarily on the 1533 version, all the while carefully comparing and contrasting it to the 1510 first edition, and the 1531 2nd edition as well as the first manuscript version Agrippa sent to Trithemius.[3] To his credit, Purdue has been careful in tracking down many sources Compagni had not worked with or located. (p. xxxvii) As a result this new edition has earned its keep as a more updated reference tool.

But when Purdue tackles various issues presented by the 1651 James Freake first English translation of the Three Books, most recently edited by Donald Tyson, the reader must pause to consider not only the significant aspects of that translation but how Purdue’s has chosen to label them as such. For instance, in one astute observation Purdue points out in Book 1, chapter 59 of the Freake/Tyson edition that James Freake confused “perfection” with profection as the latter pertains to the progression of one sign in a solar year “in a natal chart.” Tyson, by failing to return to the original Latin, adhered to Freake’s use of “perfection” thus significantly skewing the original meaning.[4] This instance highlights Purdue’s generally strong suit throughout his translation of addressing and rectifying questionable passages that deal with technical astrological terminology and concepts, no small feat given the amount of space Agrippa devotes to the matter. The attention Purdue has given to such details make these types of annotation worth the price of admission alone. Nonetheless there are instances, such as in Chapter 30 of Book II where Agrippa discusses how to determine a more powerful aspect of the moon, where Purdue’s notes could have benefited from a more basic explanation. Agrippa states that the moon should not be in via combusta, which, Purdue states, means literally “burnt way” being “a particularly negative placement for the moon.” (p. 378, fn. 9) It may be useful for the layman to know that 15 degrees Libra and 15 degrees Scorpio signifies a time when an astrological chart is too hot, hence combustible, to judge or speculate upon. This is a minor point of contention given the overall coverage of technical astrological matters in this translation.

Another important section exhibiting Purdue’s attention to detail arises in Chapter 22 of Book II with the planetary sigil for the “Intelligence of Mercury.” In his introduction, Purdue mentions that “some of the planetary seals [...] differ from the Latin original in that they are oriented incorrectly.” (p. xxix) And when we arrive at that very passage Purdue provides a very abbreviated annotation to this emblem: “The symbols in the J.F. and Tyson versions are ‘oriented’ differently from Agrippa’s Latin text.” (p. 347) This being the case, one is left to wonder about the significance of orientation and as to whether it may have stemmed from typographical constraints[5] or a glitch in the early translation. Purdue also mentions in his introduction that Agrippa describes how to construct these seals and sigils. However, the degree to which Agrippa actually outlines these seals formation is less than thorough. In fact, it was not until Karl Anton Nowotny’s article, first published in the Warburg Journal, that an earnest attempt was made to explain the rather complex, and at times convoluted method for constructing the planetary seals and sigils of Agrippa’s magical squares.[6] Granted, this is but one aspect of a lengthy work, but it is a critical matter in light of the fact that the 1531 edition is one of the first widely circulated works within and outside of the continent disclosing any particulars about the finer points of evocational magic. Given the overall length of this new translation it would be unreasonable to expect a detailed exposé of the fabrication of these magical seals and sigils. Nonetheless, an additional description providing some sense of the overall complexity of this aspect of the seals’ construction is warranted.

The question of such annotations brings us to a key aspect of a translation’s purpose and scope within the progression of a text’s evolution. According to Purdue’s Translator’s Introduction, this current edition is meant to correct the various problems and mistranslations prevalent in James Freake’s 1651 edition. In the process of pointing out these various issues, Purdue is persistent in targeting Donald Tyson’s edition of the Three Books as contributing to sustaining the problems initiated by Freake. Even though Purdue’s argument for attending to the substantive errors in Freake and Tyson’s subsequent edition is relatively sound, to imply that new and improved makes for a better overall product raises a number of concerns.

For example, Purdue, as well as Tyson, expresses an intent to rectify problems with the overall comprehensibility of the work for the modern reader. Purdue is adamant that the “archaic English of Freake’s edition is sometimes distracting or misleading.” When problems with modern parlance occur Purdue does “refer to the original Latin directly rather than modernizing an earlier translation.” (pp. xxviii-xix) In a similar vein Tyson cites an example of the text in Chapter X of Book II, that is over 8 pages comprised of a single paragraph. But then Tyson makes the claim that he has “retained the paragraphing of the original” meaning Freake’s edition and not Agrippa’s. (Tyson, Three Books, p. xliii) Purdue himself makes no attempt to adhere to Agrippa’s original format of lengthy paragraphs. Therefore, in both Tyson’s and Purdue’s case a certain degree of clarification is wanting as to their overall purpose.

If the primary thrust of this current translation is to be faithful to Agrippa’s original Latin version then a certain degree of attention needs paid to form as an extension of content and vice versa. Chapter X is but one example of the use of a single protracted paragraph spread throughout a chapter, and in fact the majority of the chapters of Agrippa’s Three Books are comprised of one and two paragraphs. Medieval Latin grammar was based on classical Latin wherein a shift in topics or subject matter was often signaled rhetorically and not by means of punctuation or structure. Furthermore, the notion of a sentence. as we think of it today, is a more recent development. In the mid ages and early modern period a sentence could signify a single topic or subject requiring an entire paragraph. And then there is the issue of how prosody factored into Latinate rhetoric. Latin was certainly the universal language of the learned throughout the mid ages that was universally employed in the west as a mainstay for scholarly and religious texts.[7] But it was a nascent language, to a certain extent, where great liberties were often taken in supplying French, German, or other romance languages to fill in the gaps where a specific Latin term was unknown, hence the moniker of neo or ecclesiastical Latin that has been employed to distinguish the medieval form from its classical or Ciceronian roots.

For the early classicists, prose could be scanned displaying dactyls, iambs, etc., to establish a melodic or rhythmic dimension of the prose for the sake of emphasis or emotive shifts in the text (the only difference being that the prose would not be metered like poetry). This mode of cursus or clausulae, as it was otherwise known, was employed by orators since early Greece. By the third century Latinate authors were employing these metrical devices for accentual purposes in texts. And, most importantly, concerning Agrippa’s world, representatives of the Vatican were employing these stressed patterns as a type of code embedded in their letters conveying a double meaning to those aware of the cipher.[8] Agrippa’s relationship immediately comes to mind with his mentor, Trithemius, who is most famous for his text dealing with a cipher, The Steganographia. Agrippa would have been more than just a little familiar with this work. Subsequently, perhaps there was a subtle type of encoding being employed in the prose of The Three Books (a topic worthy of further research). However, a modern English translation, that does not take these prosodic elements into account, along with dividing the original lengthy paragraphs into shorter ones eradicates such subtle cues inherent in the original. In fact, Purdue mentions that “the purpose of creating a new, authoritative edition […] is to take a fresh look at the original Latin.” (p. xxix) In this specific instance the view afforded is somewhat selective and comes at a cost.[9]

By modernizing and restructuring all of these particular stylistic and formative aspects of a Latinate work, quite a bit in the way of implied meaning or nuance is invariably lost. Agrippa himself suggested that “explaining the virtues of things causes the power of those virtues to be engrafted to the words spoken, and thus they act as a vehicle by which those virtues are prepared and set forth.” The integrity of the original verbal agents are undoubtedly important insofar as their implications are concerned. And in the following section Agrippa concludes that: “you must compose an ornate and elegant oration to song, with distinct resolved parts, and with agreeable numbers and proportions.”(pp. 232, 235) Agrippa emphasizes direct connection between meaning and form in carmen or magical charm and its articulation. Even though Agrippa mentions some of these devices concerning verse or chant we know such tools are not exclusively confined to poetry or what we think of as versified diction. Clearly, medieval prose was fashioned to be every bit as poetic as verse during the mid-ages. However, the quandary becomes how to present such auditory cues to the modern ear when transmuting a Latin text into modern parlance. This type of conversion may not always be economic given the dictates of producing a more streamlined or readily accessible text. New is not always improved. In any event, providing additional pointed annotations concerning the prose would have at least provided some conveyance of these factors that impact the Three Books’ translatability.

With these formal challenges in mind, the question arises: should the modern reader’s ear or eye to translated texts be challenged by somehow reproducing the original form used? Or does one placate modern sensibilities by converting the text by means of currently accepted diction into a modernized rendition at the risk of altering the rhetoric and what is being implied thereby. This is no simple question and whether or not we chooses to address such matters, or to simply bypass them, such aspects and concerns remain in the background of the work at hand. Translation depends upon reciprocal features between languages. As such, the translator’s purpose in tackling a text determines which factors receive their attention and focus. As a result, no one single translation can ever be all-inclusive in addressing a varied audience’s concerns.

So, if the translator is concerned with delivering a translation derivative of the original language, in this case, the 1531 2nd edition, then referring to the James Freake 1651 English version is almost a moot point. But if Freake’s translation is of significance, which it most certainly is for historians and students of the early modern reception of Agrippa’s work in the English speaking world, then we’ve entered a significantly attenuated arena. For centuries, Freake’s edition set the bar for how Agrippa’s occult philosophy would be perceived in the west for better or worse. Historiographically speaking, the Freake translation is neither good nor bad but a substantive artifact that must be dealt with in terms of all of its aspects, foibles and all. As such, keeping the 1651 edition on display and intact is necessary for those concerned with viewing it as a part of the integral reception of esoteric studies in the west for several centuries after Agrippa first published his three editions.

As Walter Benjamin so astutely observed, “even the greatest translation is destined to become part of the growth of its own language and eventually to be absorbed by its renewal.”[10] Based on this perspective, it’s relatively safe to say Eric Purdue’s contribution to the study of Agrippa’s Three Books is noteworthy but hardly definitive as no single translation can ever be. Initially I was of the view that what is needed is a variorum edition of the Three Books. Having a side-by-side translation along with the original Latin could prove useful as well. And if the act of translation is a mode of reading then there is room for as many translations as there are modes of understanding. The act of translating is a communal and cumulative project not confined to any one era in its progression. To view Agrippa’s work as an enduring vital organism we need to allow it room to grow but from its own specific fertile ground. In any event, Eric Purdue’s translation provides a useful additional platform from which to survey and study Agrippa’s key text.

Note: Shepard Powell, who recently passed away, is deserving of a special thanks in memoriam. As Diane DiPrima’s long time companion, he was able to direct me toward a number of things pertaining to Diane’s early work with Renaissance esoterica that I would not have become aware of otherwise.

Footnotes

[1] See Diane DiPrima, Pieces of a Song: Selected Poems, (San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books, 1973) p. 160.

[2] In her introduction to Waite’s translation of Paracelsus’ works DiPrima’s name is completely absent from the book. It would appear she was in keeping with Renaissance attitudes toward authority where authorship was not nearly as closely coveted then as it is now. It was very common for publications during the early modern period to omit authors’ names entirely as a pro forma matter of practice. The presence of the individual was of diminished importance of which Michel Foucault clearly exposed this aspect of authority and ownership. See: Parcelsus, The Hermetic and Alchemical Writings of Paracelsus, Ed. Arthur Edward Waite (New Hyde Park, NY: University Books) pp. v-xii; and Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, Ed. R. D. Lang (New York, NY: Random House, 1973) pp. 17-45.

[3] See: Henry Cornelius Agrippa, De Occulta Libri Tres, vol. 48 (Studies in the History of the Christian Tradition) Ed. Perrone Compagni, (Leiden, Switzerland: Brill Publishers, 1992) p. 51

[4] Agrippa uses the term “profectionis” which should in no way be confused with “perfection.” See: Libri Tres, p. 211.

[5] It was not uncommon for printers, in the early modern period, to literally run out of certain typefaces during a run. In such instances spellings could be altered as needed to make up for the dearth of particular characters in their trays.

[6] The fascinating thing about these seals and squares is that, according to Nowotny, aesthetics played a substantial role in their formulation. Since Nowotny, others have written on the topic but no single account of the seals formulation can actually claim to be straightforward. Nowotny, at the very least, implies that orientation is a significant aspect of Agrippa’s utilitarian concerns. See: Karl Anton Nowotny, The Construction of Certain Seals and Characters in the Work of Agrippa of Nettesheim, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 12 (1949), pp. 46-57.

[7] However, during the mid ages and early modern period classical Latin was not known in its entirety and so writers would often substitute German, French, and or Italian terms inflecting them thereby creating surrogate Latinate terms. Since this was often the case with religious texts this usage because known as ecclesiastical Latin.

[8] See: entry by Paul F. Baum for, “Prose Rhythm” in The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Ed. Alex Preminger (Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1990) pp. 666-667.

[9] DiPrima herself was concerned that the reader should not only read Paracelsus for the content but for the “beautiful prose.” There is inestimable merit to these concerns that have become waylaid in recent years with the advent of more modernized truncated translations geared toward accommodating the ear of current readers instead of working to give voice to various subtleties. As with Paracelsus, much of the magic in Agrippa’s Three Books is in the language itself.

[10] Walter Benjamin, “The Task of the Translator” in Illuminations: Essays and Relections ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken Books, Inc., 1968) p. 73.