‘The Tree of Gnosis’ by Ioan P. Couliano

Review: Ioan P. Couliano, The Tree of Gnosis: Gnostic Mythology from Early Christianity to Modern Nihilism, New York: Harper Collins, 1992, ISBN 0060616156

by Frater Acher

For readers who don't know the name Ioan P. Couliano (also Culiano), we’ll best begin with the end.

In May 1991 Ioan P. Couliano, a brilliant professor of the history of religion at the University of Chicago, a close friend and collaborator of Mircea Eliade, and a fierce critic of the autocratic political forces in his Romanian home country, was murdered in cold blood at the University’s toilet: A single bullet, fired from the adjoining stall from the barrel of a Beretta .25 pierced his head. A shot, as the medical examiner would remark later on, that wasn’t easy to accomplish, suggesting the work of a professional.

The politically motivated murder of the young high-flying professor sparked significant interest at the time. It even led to an article by Umberto Eco in the New York Review of Books and a dedicated volume by Ted Anton on the circumstances of his murder. However, the attention paid to the detailed circumstances of his death somehow seemed to distract from the remarkable new ideas Couliano had introduced in his field. Henceforth, as abruptly as the life of Prof. Couliano had ended, so did much of the influence of his radical work in the field of history of religion.

Undeservedly, today the name Ioan P. Couliano does not ring the same bells in common general knowledge such as e.g. Mircea Eliade or Gershom Scholem still do. If at all, scholars of Western Esotericism remember his major work Eros and Magic in the Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987). However, only a year before his untimely death Couliano had published a landmark study on Gnosticism. Originally titled Les Gnoses dualistes d'Occident: Histoire et mythes (Paris: Plon, 1990), it was published in an English translation by Harper Collins as The Tree of Gnosis in 1992. – Almost twenty years further on the book is long out of print, has disappeared altogether from Harper Collins’s webpage, and a book-metasearch machine is likely to find no more than 20 available copies worldwide at any time, with an average price of above 100 USD.

I suppose it would be easy to fall back on platitudes and simply affirm ourselves in the belief that if time isn’t ready for the ideas one has to present, it will find the most uncanny ways to silence one’s voice. The scenario closer to the truth, it might seem, is that this has nothing to do with time as a representation of Chronos’s devouring qualities, and yet everything with the lack of readiness in the academic establishment to embrace challenging and divergent ways of thinking: Even today, reading The Tree of Gnosis can feel like a full-frontal attack on many of the common myths and stereotypes that still exist to this day in the history of Gnosticism. Couliano writes with a “take no prisones” approach, and yet the poignancy of his voice is always grounded in the elaborateness of his detailed research and knowledge of original sources.

That Iran was the homeland of dualism would become an extremely elaborate and fashionable hypothesis with the German school of history of religions […], whose most important representatives were Wilhelm Bousset and Richard Reitzenstein. […] Today they appear as one of the most maskable organized and highly acclaimed scholarly blunders of this century […]. (p. 26)

It was one of Gershom Scholem’s favorite ideas that early Jewish mysticism was a form of Gnosticism. It is easy to see that this is not so: multiplication of heavenly angels, watchwords, and seals is something some gnostic texts have in common with Merkabah mysticism, yet it is neither gnostic nor Jewish. It is common Hellenistic currency that circulates among the magical papyri as well. If we were inclined to search for “origins,” the late Egyptian derivate of the Pyramid and Coffin texts known as “The Book of the Dead” is probably the closest we would get. (p. 42)

Couliano encouraged a radical departure from the now outdated work of many great minds that had come before him. However, this departure did not only pivot on a much more thorough reading of now accessible, mainly interdisciplinary sources; instead it focused on a radical paradigm shift with regards to how we understand history itself.

Couliano postulated that endless historic analysis to pin down precise transmission pathways of ideas from culture to culture, continent to continent, or one area to the next, was ultimately not only a fruitless attempt, but essentially an inadequate method for the actual problem at hand. He wanted to replace the traditional historical method with a new kind of approach to studying history which he termed morphodynamics.

And this is precisely the place where we encounter a fork in the road on how we can choose to read The Tree of Life: It is perfectly possible to study the first three sections of the book (Introduction, Dualism: A Chronology, and Myths About Gnosticism: An Introduction), then to skip over the main body of the book, consisting of a masterly analysis and comparison of gnostic cosmologies, and to join the current of Couliano’s exegesis again with the three closing chapters (The Tree of Gnosis, Modern Nihilism, andEpilogue: Games People Play). Alternatively, we can also open ourselves to the broad horizon of detail and information presented within the seven middle chapters. The former approach will anchor our focus on a proper understanding of morphodynamics, whereas the latter will present us with a firework of historic details, spiritual correlations and social power dynamics amongst the many schools and factions of Gnosticism. Whichever way of reading we choose for this book, it is unlikely that we will emerge from it unchanged.

Here, in this review we will focus on Couliano’s innovative concept of morphodynamics and attempt to provide a high-level introduction to this unfortunately still little known method of examining our collective past.

As so often with radical new ideas, the essence of morphodynamics is explained quite quickly. Yet once this is done, it is likely to take a surprising amount of effort to apply this novel way of seeing the world to one’s own life and professional studies. As we all know, habits of the mind can become cobwebs of steel, caging us in mental frames that don’t allow for easy escapes.

Couliano’s method pivots on the postulation of what he calls ideal objects: Think of Plato’s eternal ideas but consider them interdependent hive beings which reside in a higher dimension than our three dimensional world. These ideal objects, seen from a human vantage point, are perceived to be astonishingly complex, very hard to pin down in a solid form, and yet incredibly long-lasting over periods of time. In fact complexityis one of the conditioning factors for an ideal object (p. 13). Equally, from a human vantage point the ideal objects will appear as ideas or logical problems, as structural patterns of the mind; and yet the idea itself is only an artefact created by the encounter of a human mind touching on an ideal object.

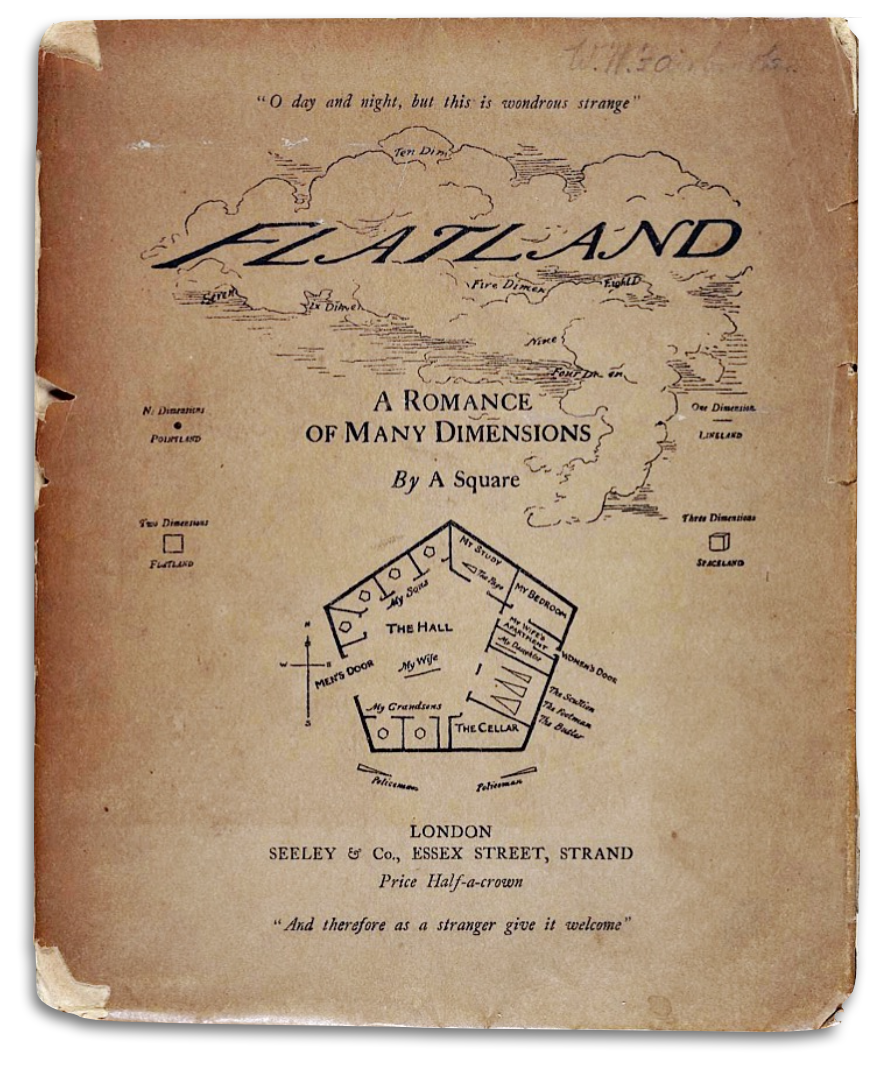

In a stroke of genius, Couliano now illustrates this concept by borrowing from Albert Einstein; and more specifically from a source quoted by Einstein in his Theory of Relativity [Albert Einstein, Über die spezielle und die allgemeine Relativitätstheorie (Gemeinverständlich), Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1916]. This source is Edwin A. Abbott’s famous novel Flatland - A Romance of Many Dimensions, told by A Square (Edwin A. Abbott: Flatland: A romance of many dimensions, London: Seeley, 1884).

In the following, we are quoting the adopted passage from The Tree of Gnosis in full, as taking this analogy seriously holds such wide-ranging implications for the study of not only history, but especially the history of spirituality and magic in particular. Even though it runs the risk of unfairly diminishing the vista Couliano opens in later chapters on the historic details of Gnosticism, his innovative transfer of Flatland (or Souplandas he calls it) to the study of history has the potential to outshine the rest of the book:

The most extraordinary consequence of the Einsteinian space-time continuum for the historian of ideas is the existence of “ideal objects” which become understandable only when they are recognized as such in their own dimension. This may sound even more incomprehensible than Einstein’s universe. To make it understandable let us revert to Flatland, and suppose that the flat country is the surface of the soup in a dish. Let us suppose that the circles of oil on that surface are the intelligent inhabitants of Flatland. Obviously, being two-dimensional they can move in two directions only: left-right and forward-backward. The direction up-down is as meaningless to them as would be a new direction to us, toward an unknown fourth dimension (the mathematician Rudy Rucker calls such a direction ana-kata). What they see of each other is a line, any space (such as a house or a bank) being closed to them by a line only. Yet, seeing them from a third direction of space, we can directly see their entrails, the interiors of their houses, and we could easily steal from their most well guarded bank safe. (As strange as it might seem, a being in a hypothetical fourth dimension of space would equally enjoy these advantages relative to us.)

Let us now suppose that I disturb all this flat world by starting to eat the soup with a spoon. How would a Souplander experience the spoon? He or she would be horrified by a strange phenomenon. First a rather short line, corresponding to the tip of the spoon, would appear in Soupland, which would increase as the spoon reaches for the bottom of the dish and would decrease again when the handle crosses the surface. Then, all of a sudden, a tremendous soupquake would take place, and part of the world would be absorbed nowhere. The disruption would continue for a while, as soup drips out of the spoon and crosses Soupland, then their situation would revert to normal.

To the Souplander, the spoon does not appear as a solid, vertical object, as it appears to us. Souplanders can experience the spoon only as a series of phenomena in time. It should not come as a surprise that life expectations are rather short in Soupland. Therefore it would take millions or billions of generations of Souplanders to make sense of the spoon phenomena. And it would take a genius of uncommon depth to make calculations that would show that the only way to put them together would be to postulate the existence of a superior dimension — the third — in which objects of an unknown sort exist. (Since they cannot possibly see us, even the most intelligent of the Souplanders would probably believe that the third dimension is just a mathematical fiction that serves only as a heuristic device.)

Similarly, we fail to understand what phenomena may be in spacetime (and what “history” really means), especially when the objects of our inquiry are not tangible. Many do not even believe a “history of ideas” to be possible, let alone a history that would not be mere summation but something having to do with “space-time”! Yet the novelty of the multifarious methods that belong to the cognitive approach was to show that ideas are synchronous. In other words, ideas form systems that can be envisaged as “ideal objects.” These ideal objects cross the surface of history called time as the spoon crosses Soupland, that is, in an apparently unpredictable sequence of temporal events. (p. 2-3)

Umberto Eco in the above quoted review does everything possible to posthumously save Couliano’s name from the suspicion that his private interest in magic could have stained the precision and validity of his work as an academic researcher. And yet, even Eco admits that Couliano was “already proceeding along the dangerous paths of magic” (link).

In light of this, we grant ourselves permission for a short diversion: We believe it is no accident that the fable of Soupland holds such critical relevance if further transferred to the field of magical practice. In fact, as practitioners ourselves, exploring this parallel might help us embrace his concept of “ideal objects” in even more organic ways.

Most encounters of magicians with spirits happen in the mind of the magician. As Agrippa of Nettesheim was taught by Johannes Trithemius and later on put down in his De Occulta Philosophia, as magicians we devote the majority of our work to attuning ourselves to particular spirits (think: ideal objects) only to be able to encounter their voices within our own minds. Two sections in Agrippa’s magnum opus are of particular interest in this context. Let’s note how easy it would be to read them as a 16th century man’s description of a human’s interactions with ideal objects as expressed by Couliano:

The Philosophers, especially the Arabians, say, that mans mind, when it is most intent upon any work, through its passion, and effects, is joyned with the mind of the Stars, and Intelligencies, and being so joyned is the cause of some wonderfull vertue be infused into our works […]. But know, that such kind of things confer nothing, or very little but to the Author of them, and to him which is inclined to them, as if he were the Author of them. And this is the manner by which their efficacy is found out. (Agrippa of Nettesheim, Three Books of Occult Philosophy, Book I, Chapter 67, London: Gregory Moule, 1651)

But now how Angels speak it is hid from us, as they themselves are. Now to us that we may speak, a tongue is necessary with other instruments, as are the jaws, palate, lips, teeth, throat, lungs, the aspera arteria, and muscles of the breast, which have the beginning of motion from the soul. But if any speak at a distance to another, he must use a louder voice; but if neer, he whispers in his ear: and if he could be coupled to the hearer, a softer breath would suffice; for he would slide into the hearer without any noise, as an image in the eye, or glass. So souls going out of the body, so Angels, so Demons speak: and what man doth with a sensible voice, they do by impressing the conception of the speech in those to whom they speak, after a better manner then if they should express it by an audible voice. (Nettesheim, 1651, Book III, Chapter 23)

As indicated by Agrippa, the essential work of the magician results in operations which often are entirely invisible to the outside (in our three dimensional world), and yet both highly specific and complex on the inside. As Frater U∴D∴’s models of magic taught us decades ago: Any magician should feel at liberty to engage with the world in the way that yields the most effective results. Thus, whether we choose the labels of “spirit” (i.e. animistic model) or “ideal object” (i.e. philosophical model), might matter more with regards to the audience we like to capture, than the reality we are describing.

According to Couliano, thus Early Christian Theology, Western dualism (p. 267), or specific aspects of Gnosticism (e.g. creationism, reincarnation, traducianism) should be considered as ideal objects. Again, we are likely to be reminded of the concept of egregores in Western Magic when reading Couliano’s practical application of ideal objects in academic study:

As such, they are atemporal and ubiquitous. They do not “originate” in India or “cross” Iran; they are present in all human minds that contemplate them by contemplating the problem. May this serve as a clear illustration of our view of “genesis” and “cognitive transmission” of ideas, as opposed to the view of a certain elementary historicism. (p. 58-59)

As mentioned above, we haven’t even touched on the main body of the book concerned with the history of Gnosticism. And yet, we are already knee-deep in cognitive dissonance and reconsidering many things we might have taken for granted: According to Couliano’s ideal objects, the mathematical terms of field, relativity or uncertainty take on an entirely new practical meaning for the study of the history of ideas. Applied to Gnosticism as well as any other spiritual tradition with its myriads of offshoots and orders, the very notion of man-made orthodoxy turns into idiocy. For as Souplanders ourselves, at best we can hope to provide an accurate description of phenomenology, but never to make any universal statements on ontology. Incidentally, it may well be argued that this is actually what Postmodernism in its entirety is all about.

Immersing oneself into the broad middle chapters of Couliano’s book on Gnosticism will make any believer in a clear source of spiritual orthodoxy risk their virginity. Getting close up to the divergent strands and schools of Gnosticism, being forced to see so much flawed logic and lazy abstraction side by side, and yet each minority group being deeply entangled in violent infighting over more than three centuries, who could come out of this still believing that codified spirituality, filtered through man-made institutions, has anything left to do with divinity, and yet everything with social power? Clearly this was the conclusion Couliano himself arrived at (p. 267).

And yet, while stunned by the abundance of short-lived and ill-fated eschatological schools, what Couliano presents to the reader in crystal clear light is the emergence of several ideal objects, untouched by time and space, creating fractals and myriad traces of themselves, each time their spoon touches the soup…

While the ideal objects remain untouched by time and space, it is their experience through the human mind, bound into time and space, that opens the broad field of morphodynamics: the study of the fractals and countless self-similar solutions generated over millennia of time by the encounter between humans and ideal objects.

Now, where Couliano could have been more precise in his articulation, is precisely in the above point, i.e. in differentiating his original concept of ideal objects (think: spirits) from the way these are encountered or processed by the human mind (think: magic). While his essential point is clear, we find him struggling in sharpening this relationship of object and human experience of the object up until the last pages of the book.

Amongst ideal objects, or mind games played with ideas, it is thus predictable that not only religion also but philosophy and science are games entirely similar in nature and built on the same binary principles.

[…]

therefore systems that have been sufficiently run in time would tend to overlap not only in shape but in substance. With complex data at hand, we should be able to demonstrate that portions of the map of the Buddhist system would overlap with portions of the Christian system with portions of German idealism with portions of modern scientific thought, because all systems are infinite and tend to explore all possibilities given to them. Accordingly, when sufficiently extended, their maps of reality would certainly coincide. (p. 268)

In essence, a concluding definition of any ideal object eludes human capabilities. As we are dealing with entities of a higher dimension, it is sheer impossible for us as beings of a lower dimension to make ontologically precise and comprehensive statements about them (p. 2).

What we thus need to focus our attention on is not the ideal object itself but the human experience thereof: Whenever humans touch on an ideal object, what they actually experience is a strong cognitive tension (think: Agrippa’s passion) connected to an essential logical problem. The answer formulated to this problem is not the ideal object itself but a man-made reflection of its imprint, thus bound to continuously evolve over time. Accordingly, Couliano considers that ideal objects when coming into contact with human minds are likely to generate fractals (p. 267) i.e. self-similar solutions or “bricks” that can be stacked in endless ways to resolve the mental tension of experiencing the essential problem.

“A masterpiece of scholarship.”

Ultimately, The Tree of Gnosis does not only present a masterful investigation into the complex history of Gnosticism – the book introduces us to a broader, much more challenging vista from where we can see ourselves, that what is truly at stake here is no longer Gnosticism, but “the meaning of history itself” (p. 255).

In a nutshell: The roughly 100 USD we need to invest to gain access to this forbidden tree of knowledge are well worth the investment. Most likely, coming out of this encounter with the brilliant mind of Prof. Couliano, we’ll find ourselves equally overwhelmed and shattered as well as delighted and inspired to take a fresh look at any spiritual tradition, or all of history for that matter.

Further Online Resources:

Umberto Eco, Murder in Chicago, New York Reviews of Books, August 1997

Ted Anton, The Killing of Professor Culianu, LinguaFranca 1992

Sorin Antohi, Exploring the Legacy of Ioan Petru Culianu

Online Lecture: Culianu's Approach to the History of Religion

Anonymous, Fractals & Religions, Negura - Central European Ideological Magazine