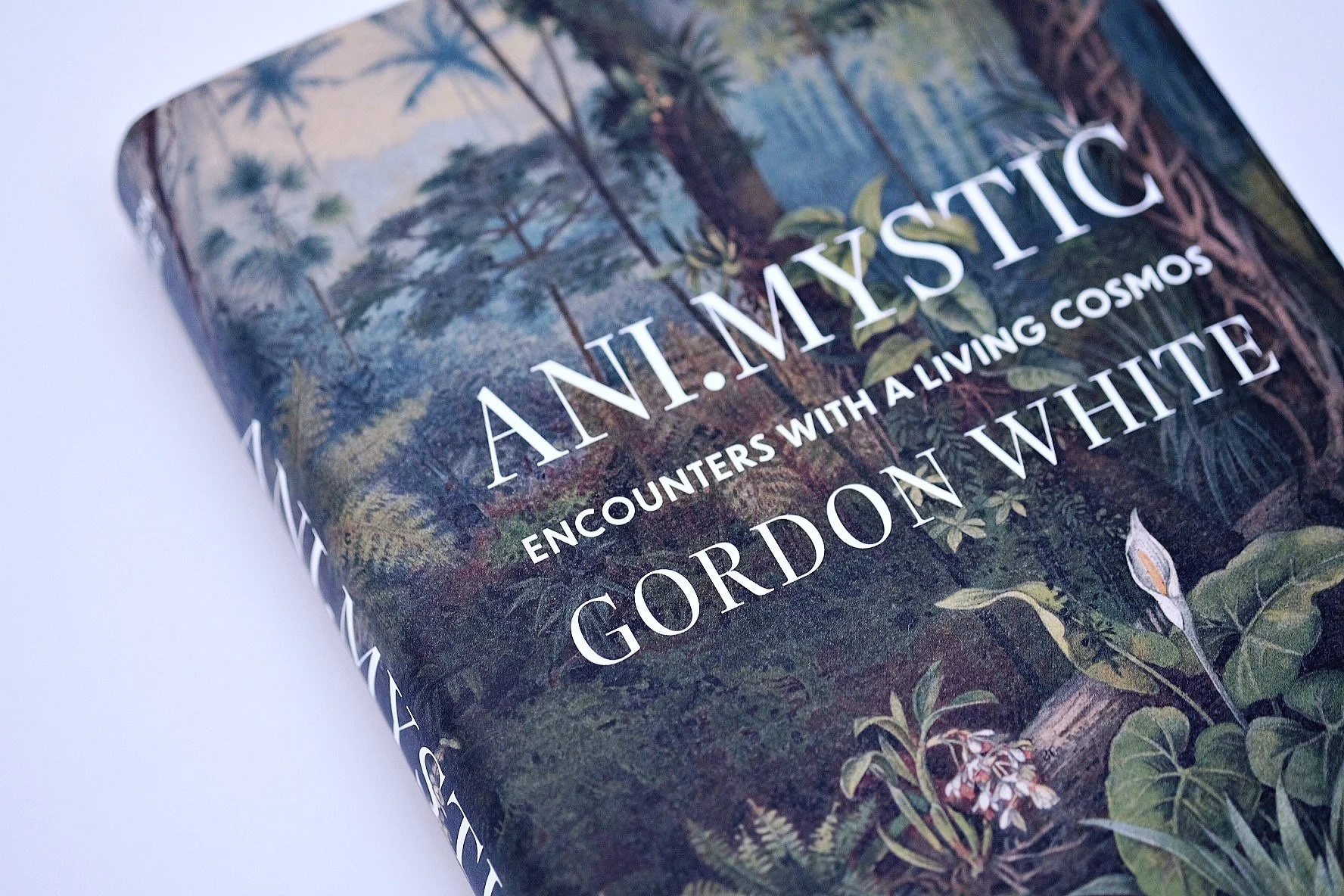

‘Ani.Mystic’ by Gordon White

Review: Gordon White, Ani.Mystic: Encounters with a Living Cosmos, London: Scarlet Imprint, 2022, ISBN 978-1-912316-58-8 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-912316-57-1 (paper)

What is required is not a revolution in energy efficiency but a revolution in love, a fundamental shift in first principles, away from techno-solutionism and materialist-naturalism toward animism, toward the profound, felt understanding of the relationality and interconnectedness of all things. (p. 41)

With these words, Gordon White transports us to the very heart of what is, in essence, a beautiful and profoundly inspiring work. Ani.Mystic: Encounters with a Living Cosmos reminds us, from the outset, that the animism alluded to in the title is a distinctly Western framework; one that evolved to describe the beliefs and practices of those deemed ‘primitive’ in earlier ethnographic encounters. The term now serves as a timely reminder of the vastly more intricate worldviews of indigenous community’s multi-dimensional engagement with their environment but also provides “a vector for an improvement in ‘our’ ways of being in the world.” (p. 12). And as such, it serves as a pivotal concept in grasping the book’s import. The animism alluded to in the book’s title encompasses such elements as,

[…] a living cosmos incorporating an immanent spirit world, of multiple epistemologies operating in frictionless and non-extractive ways, in which beings are relationally composed toward the cosmic aim of mutual flourishing. (p. 14)

In a series of piquant vignettes – pitching indigenous discourses from across Australasia against modernity’s positivist techno-narratives (dubbed “materialist-naturalism”) we are provided with a poignant reminder of how much we have lost in terms of our understanding of, and relationship with the very notion of a living cosmos. On a more positive note, these cameos are also empowering; they highlight just how much each person stands to gain from re-aligning their worldview to encompass the lived realisation that we – along with every natural element of our sentient, self-aware environment – share and participate in the co-creation of this cosmos.

Gordon White’s interlocutors are not only the indigenous peoples that he encounters on his journeys; but those fellow explorers who have passionately articulated the various complex strands of animist discourse: Whose presence, ‘in situ’ as it were, as part of the unfolding conversations, immeasurably deepens and enriches the reader’s experience whilst contributing valuable avenues for further research. It is another significant plus for this book that we are thereby introduced to some of the most significant and thoughtful voices within this space. The work is further enriched through its geographically diverse settings, characters, their variegated discourses, anecdotes, observations, and conversations such that it is impossible, in the space of a review such as this, to do justice to its narrative richness other than to highlight some of its key conceptual underpinnings, diverse threads and themes.

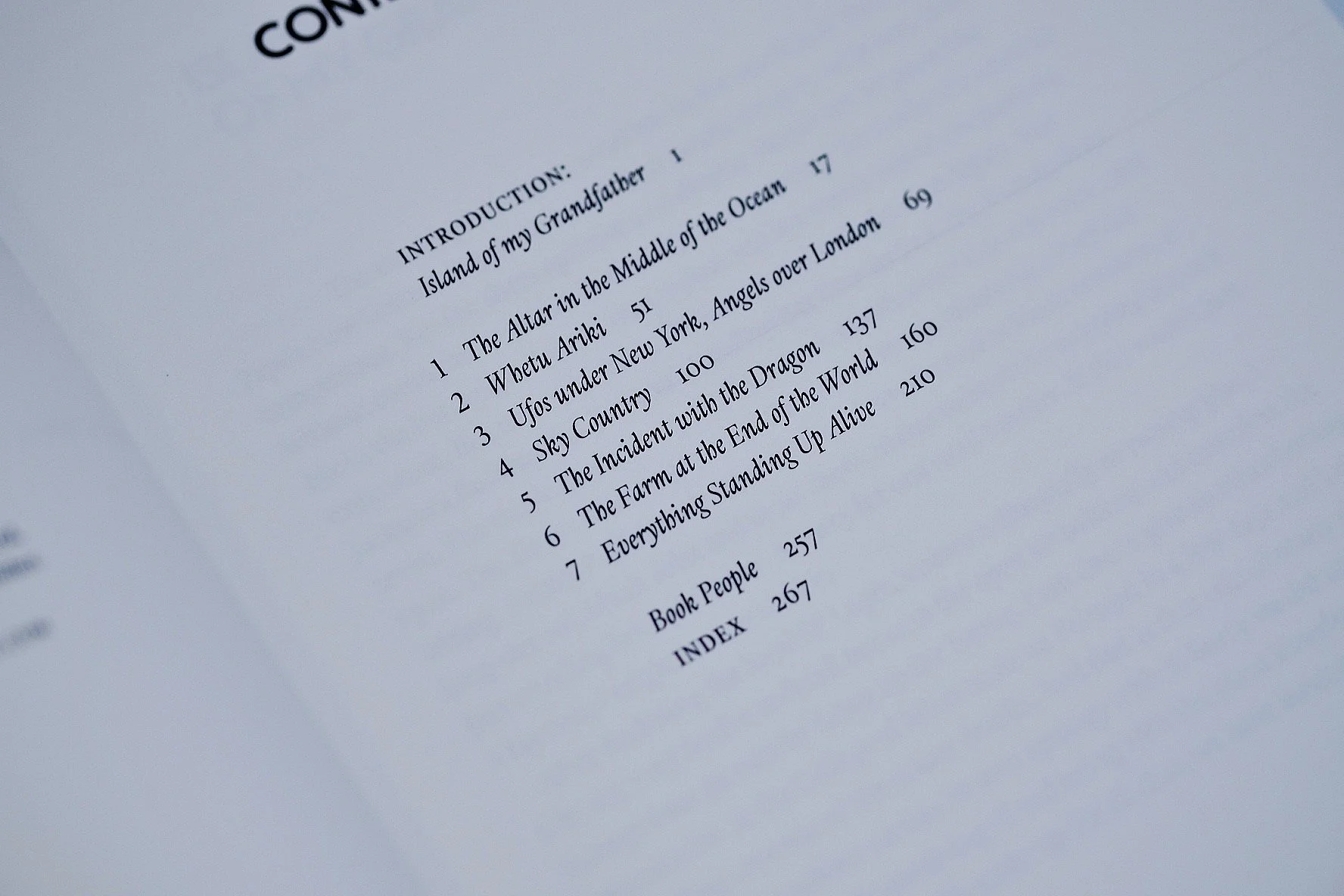

In the Introduction, The Island of my Grandfather (pp. 1-16) the author, en route to Pohnpei in Micronesia to give a lecture on ‘ethno-botany’ to indigenous students – an irony not lost on the author – contemplates the history of the island; its geological evolution, its colonial past and its neo-colonial present, extractively exploited by mining companies. He does so, however, from a geological or “Deep Time” perspective, that prompts a reflection on that great constant, change itself; and the immeasurable timescales through which landscapes, cultures and peoples have endured, evolved, and adjusted,

Thinking with Deep Time, the timescale of geologic events, is not an erasure or diminishment, but a framework that, used correctly, can make space for healing and optimism […] Any approach that understands agency as a property of the universe which contains humans, rather than a feature of humanity is an invitation to right relation. (p. 2-3)

Chapter one, the The Altar in the Middle of the Ocean (pp. 17-50), introduces the idea of a “great separation”; the process, “at first gradual, and then suddenly” (p. 21), whereby the conception of an essential personhood imbuing all reality was eclipsed in Western thought; and then conveyed, through mercantile and imperial ventures, to encompass the rest of the world; rendering it conceptually fit only for extractive exploitation – thereby inaugurating, “our cosmological estrangement” (p. 23). Whilst the processes – intellectual, technological, social and economic – that produced this centuries-long “estrangement” constitutes entire disciplinary areas in their own right, they are only touched upon in the present work since they are not germane to its immediate, and far more compelling, purpose: that of recalibrating our awareness towards the lived experience of relating to reality as actually imbued with personhood. An intellectual and empathic shift that is surely essential as we live beneath the ever-deepening shadow cast by an ongoing extinction event that remains barely visible to the vast urbanised population of the planet.

Chapter two, Whetu Ariki (pp. 51-68), introduces us to a concourse of indigenous voices, engaged in profound processes of contemplation and “deep listening”. Voices that allow us, if somewhat vicariously, to see how we might better attune ourselves to the lived reality of an animist outlook and worldview. We encounter Marcus Matawhero Lloyd, who spent six months contemplating a project to restore an ancestral hillfort – a contemplation dedicated not to the economic or logistical demands of the undertaking; but rather to a contemplative conversation with the ancestral spirits and spirits of place as they search for mutual understanding and consensus; one that honours the inherent sacrality (tapu) of both the place and of the undertaking. This account forcefully highlights any distance that may exist between ourselves, and someone thoroughly immersed in an animist worldview despite the fact that such deep listening, “may look unfamiliar to many of us, but it is positively quotidian to most of the world” (p. 52).

Difficult as it may be for us to imagine conducting such an extended, six-month long discourse with disembodied spirits to better harmonise our relationship both with our ancestral past and the land, this example bids each of us to seek out that “deep spring within” and learn to cultivate that quality of “deep listening and quiet”, whose operation is such that,

We call on it and it calls to us [...] I can sit on the riverbank or walk through the trees; even if someone close to me has passed away, I can find my peace in this silent awareness. There is no need of words. A big part of dadirri is listening. (p. 52)

This style of tuning in to one’s ancestral community, as well as to the other-than-human inhabitants who populate every tree and blade of grass of the environment, involves a disruption to our habitual ways of seeing and interacting; a “postactivism” that, in the words of Bayo Akomolafe,

[…] turns ‘things’ like la(ws and basalt ruins and the weather back into ‘persons’ and in so doing frees humans from being the sole source of agency in the comings and goings of the world. (p. 50)

To do so, Akomolafe avers, “opens up room for other places of power” (p. 50). For it is only in the domain of power, wherever that may lie, that redress is to be found.

Chapter three, UFOs under New York, Angels over London (pp. 69-99) takes us, somewhat unexpectedly, to the basement of the Guggenheim Museum in New York for a detour into UFOlogy. It is not, however, as strange a turn as we might at first suspect. Given that UFOs (alongside every manner of spirit being) form an integral part of the visionary world of indigenous peoples the world over, a question mark naturally arises over our own discursive framing of this phenomenon – typically as a technological challenge or a morbid psychological anomaly. In the author’s mind, however, it gives rise to a different question.

What cymatic transformation in ufology and technology may appear in the sand if the plate of western discourse is subjected to an animist vibration rather than a materialist-naturalist one? (p. 69)

Despite being confronted with incontrovertible evidence, modernity’s perspective on the phenomenon contrasts sharply with that of indigenous communities whose longstanding awareness and acceptance of “star peoples” as constituting a significant aspect of an already teeming other-than-human reality. One that routinely intersects, and on occasion, interpenetrates, our lived experience. A fact that raises, in a particularly acute form, modernity’s disconnect from the vast cultural continuum of human experience and raises once more the issue of “right relation” – an issue that runs like a leitmotif throughout the entire work. One aspect of which, epistemic closure, curtails the dynamic range of modernist knowledge as though the lens of our awareness is a fixed aperture.

The drive to ‘complete’ a fact or understanding is very much Enlightenment thinking, as it suggests that the world is fully formed and all that remains is for us to ‘know’ it. Animisms rely on contingent knowings, frameworks of understanding that allow for the universe to be alive and transforming, not fixed or complete. (p. 73)

The crux to turning around our desperate estrangement lies in the scope or inclusivity – personal, social and legal – afforded to our notions of personhood. In this context we are introduced to anthropologist Viveiros de Castros’s ethnographically borne insights gathered under the rubric of “perspectivism”:

[...] the personhood status of all beings is the foundational ‘stuff’ of the cosmos. All beings perceive themselves and the world the same way we do, and they see themselves as human persons. How they perceive other beings also follows this underlying logic of personhood. (p. 76)

The lived recognition of this, the “common and original ground of being” (p. 77), shared with all sentient life is, perhaps, that one lever which has the power to shift our entire conceptual universe, for if,

Every relatable being is conceived of having a soul of ‘human’ character. If the whole universe is alive or made of ‘soul stuff,’ then it is not the differentiator. It is the body itself that gives rise to multi-naturalism. It is produced out of soul – as everything is – but also against it because a being has to differentiate itself from all that there is. (p. 77)

Ultimately, we are challenged to adapt to a vision of reality, “which de-exceptionalises the human back into the cosmos” (p. 76)

Chapter four, Sky Country (pp. 100-136), conveys us to the vastness of Ulurnu, the endless vistas of the desert-like landscapes of Central Australia, to investigate the continent spanning the “Seven Sisters songline”. We learn that the term “songline” was not, originally, an indigenous term at all; but rather a neologism coined by travel writer Bruce Chatwin as he misconstrued the ethnographic significance of the landscape-imbued indigenous creation myths that he encountered; framing them, functionally, as beacons for navigating what appeared to his Western eyes as an otherwise tractless terrain. Despite the term’s subsequent adoption by indigenous people, the ambiguity surrounding the role of the myth-cycles in relation to the lived experience of the landscape remains integral to its continued relevance and reflects the expansiveness of the underlying reality that it points towards.

[…] because songlines is a translation term that attempts to define what is essentially undefinable, its meaning will always harbour ambivalence, imprecision and elusiveness, but this is also the case with ‘Tjukurpa’ which conceals as much as it reveals. (p. 103)

“Tjukurpa”, or dreaming, also conveys that ambiguity; that otherworldly quality of an awareness attuned to other frequencies of a vibrant, living, breathing reality. In this context we learn that these extremely ancient song-cycles serve to preserve environmental relatedness, point us towards other ways of seeing and being, but at the same time remain responsive to and adaptive of modern technology, a point that serves to illuminate the fact that,

When westerners problematically seek to learn from ‘indigenous wisdom’ we typically expect antiquity when what we should be ‘learning’ is adaptability and continuity. It is not that ‘indigenous wisdom’ is old, per se, but rather that it has sufficient responsiveness to have lasted. (p. 103)

The lesson is reinforced by the realisation that archaic myth springs eternally fresh from a deeper reality, for anyone, that is, who takes the time to contemplate it. For the time of myth itself is only accessed when we allow our awareness to slip towards its deep a-causal logics, its synchronicities and timeless, eternally cycling nature. The author’s meditation on time takes him further afield to explore the cosmic nature of time itself and the synchronisation of units of measurement, scaled from the very smallest to the very largest, across diverse cultures, objects and places and encompassing everything from Platonic Solids to Cosmic cycles.

The experience of or encounter with these numbers is ‘something like’ a conceptualisation of time that allows for the felt presence of the distant past and the distant future within the experiential timeframes of a human lifetime. [...] Animist astrology is an invitation to right relation with time as a being as well as itself being a relational language with all other beings […]. (p. 129)

Consideration of which leads naturally to the many indigenous discourses concerning their ancestral descent from and interactions with star peoples and UFOs. Interactions that range across the phenomena variously reported in Western contexts but now situated within the body of a community’s ancestral memory, expertise and understanding.

Among the Maya that Dr Clarke encountered, they almost universally considered themselves as being from the stars. The Aṉangu experience ‘something like’ this reality where the stars are the campfires of the ancestors. (p. 135)

Chapter five, The Incident with the Dragon (pp. 137-159), commences with a discourse on “journeying” (the non-physical perception of distant times and places, known under many different rubrics across a variety of traditions and cultures) and introduces the author’s struggle to discern the spiritual forces involved in the fearful events surrounding an immense forest fire that threatened to engulf the entire state, including his farm; and how, through the collective “magical” effort of his extended network of contacts – both embodied and disembodied – it stopped just at the edge of his property. The perception of spiritual forces acting in relation to physical events – such as a great fire – along with the ritualised plea for the intercession of other spirits to curtail it, is one that is guaranteed to test the depth of most people’s animist convictions. The further difficulty that the author raises is that of interpreting the status of his own vivid visionary experiences.

What kind of metaphor is this once I return to the walking world and cross the metaphoric divide? (p. 143)

The practical outcome of these efforts was to engage with a committed group in an “intention experiment” – though this was no experiment proper, but an all-out effort to influence the increasingly dire turn of events on the ground – à la Lynne McTaggart’s The Power of Eight. The ceremony itself induced feelings of pressure akin to diving underwater at night,

[...] the sensation of being somewhere that dark and pressurised, the gloom lit only by the murky green and ruby lights of what I presumed to be the jewels on the foreheads of the denizens of Nāga-Loka as they slowly became aware of me and began to circle me like five-hundred-foot eels. (p. 152)

On the day on which the author had expected it to rain (despite there being zero meteorological chance of that happening), “It poured down with a force that would have extinguished the fires of hell” (p. 157) and the state, along with the farm, was saved.

Chapter six, The Farm at the End of the World (pp. 160-209) is essentially an account of the background to the author’s dreamt-into-being permaculture farm in Tasmania and an elaboration of the diverse threads – originary, metaphysical, agricultural, political – of its presence on once contested land. Concerning permaculture, we learn that,

[...] the name was formed in response to the realisation that a culture or agriculture that uses three units of energy to generate one unit of food energy is anything but permanent. Point of fact, it is guaranteed to one day end. (p. 162)

The questions that the author poses, however, are less about permacultural practices (which are not addressed) but rather about what permaculture is when viewed through an animist lens. When we consider,

[...] the lines of the non-human inhabitants who contribute to the knot of a place. The trees, the birds, the spirits, the ancestors, the snakes, the restless dead […] if each place has a Dreaming, then we should see this show up as the anomalies within materialist-naturalism’s anomalous data. (p. 165)

Given Tasmania’s dire colonial record – one of expropriation, murders, massacre and ethnic cleansing – and given that, “Place, time and meaning are all co-implicated in each other’s emergence” (p. 167), then the great fire described in the previous chapter, in which the spirits of place are said to have been either directly implicated or at least mute in the face of entreaties for their assistance, should, based on an animist perspective, hardly surprise us. Was not the fire both an apt metaphor for and expression of that anger, sadness and fear arising from the pain of origin?

That place is some kind of ‘real’ thing is in most respects wondrous. But it also consequently comes with the stark realisation that the inertia of cruelty is in and all about us, and that this is something with which we must all come to terms [for] […] contained in the knot that it is, are the threads of land theft, violence, and cultural destruction. […]arguably the site of the British Empire’s most successful genocide. (p. 167/171)

All of which raises a fundamental question that could be asked of so many places where, over time, the most awful events have been enacted leaving the land imbued with a lingering darkness, and posing that most severe of questions to those who dwell on or near such places, especially those who might espouse a higher purpose,

Where does that leave a magician – or any of us, really – recently in possession of damaged, stolen land? (p. 172)

There is, actually, no escape. Or as William Faulkner put it, “the past is never dead, its not even past.” The author recommends, “staying with the trouble – forming those unexpected collaborations and combinations – always includes the spirits of colonial impact” (p. 174). We can add the possibility of healing such ancestral ruptures through such endeavours as systemic constellations, for then the ethical violations that haunt subsequent generations can be repaired; and that this is, from an animist perspective, an imperative, since, “Getting right with the Dead makes the world better.” (p. 175)

Chapter seven, Everything Standing Up Alive (pp. 210-256) commences with the heartfelt insight that,

the shaman is in the business of healing, not of curing. Curing is the removal of symptoms. Healing is an experience of the infinite. (p. 213)

The core of the chapter is taken up with a series of five ayahuasca ceremonies that the author undertook in the Peruvian jungle. An experience common to those working with beings such as Ayahuasca (capitalised, as the author recommends, to distinguish the presiding, higher order being from the plant or the ceremony of that name; though all three remain intimately connected) is that their presence precedes, and overshadows, the actual commencement of the ritual process and is associated with the articulation of intent in conjunction with the shaman’s preparatory work. Accordingly, the author describes how,

It felt to me that Ayahuasca ‘landed’ about three hours before we were due to go to the maloca [ancestral longhouse] […] As if some large and ancient being descended somewhere near the river and made its way toward the place of ceremony. (p. 216)

Of the experience of participation in the two weeklong ceremonial healing process it is impossible, within the scope of a review such as this, to do more than give the briefest of sketches, given the dynamic, emotionally and metaphysically profound nature of its interlocking, inter-dimensional nature.

I was pulled out of my body and sailed above and up the river upon whose banks the camp was located. The dark shapes of trees, shrubs, logs and rocks burst into bejewelled splendour as I floated past, each being not only aware but glorious and inhabited. The trees were beings in their own right, and they were also the houses of myriad different forest spirits. (p. 218)

The descriptions of the various visionary states that unfolded are reminiscent of the vivid, electro-coloured, teeming spirit worlds familiar from the artwork of the Peruvian Ayahuasquero, Pablo Ameringo, that more than affirm the truth that,

[…] deep-forest dwelling people understand that the entire material dimension is maybe one hundred trillionth of all Creation, a tiny physical fraction embedded in a much larger relational web of spirit. (p. 218)

The ayahuasca ceremony sensitises the visionary to acknowledge the deeper aspects of reality – in this case the existence of a deeply ethical dimension integral to our participation in a living cosmos,

[…] something hears you every time you express a hostile thought at someone. We enter into thousands of little pacts each lifetime that trap and impede our energetic flow. (p. 228)

Moving now towards the end of the chapter, and of the book, the author confronts a fundamental question that is also, perhaps, the fundamental question underpinning the positivist outlook; an outlook responsible for our continued “cosmological estrangement” (p. 23), the failure to grasp the nature of consciousness and, indeed, the nature of nature herself:

[…] what is it about the materialist-naturalist epistemology that makes it different to all others mankind has birthed on our journey so far? (p. 238)

In a bid to address this central question we are introduced to Tim Ingold’s idea of “wayfaring” as “our most fundamental way of being in the world” (p. 239); a mode of being and relating to the wider reality such that,

Wayfaring is what happens when you travel through rather than on the world and meaning-making occurs during and with this process. (p 239)

In a word, it is the level and depth of our empathic engagement with a living environment, that “right relation” which we have referred to so many times, that generates the quality of situated, intimate knowledge that this work captures so well, and in so many diverse contexts. Citing Eduardo Viveiros de Castro earlier in the book the author frames the animist perspective,

[…] animism is not a belief system but an ‘interpretive convention’ that ‘personifies the objects of knowledge’ – including thoughts – so that thinking becomes ‘an activity.’ It is not a mental state (collection of fixed ideas and feelings) but a theory of mind (way of thinking). (p. 59)

So that,

Wayfaring past this materialist-naturalism requires being guided by constellations of other knowledges to seas that are endlessly forming rather than fully formed, to encounter vibrant, living, open-ended islands. Wayfaring is moving through a completing world. (p. 242)

Finally, Chapter eight, Book People (pp. 257-266) usefully provides short biographical and bibliographical entries for each of the author’s main interlocutors.

Ani.Mystic is a beautiful and informative work. But to read it is to embark upon a densely woven encounter. The sheer variety of voices that contribute to its fabric do not obfuscate, in any way, its message. Rather, they serve to pitch a distinctly perspectival challenge to the reader, to ingrained habits of thinking and being, as we attempt to straddle the linear logic of the book’s arguments and the vertical dives and ascents occasioned by encountering worlds and worldviews beyond the consensual dream of our daily reality. We may also feel challenged in our greater limitedness, our alienation from the more nuanced visions of those who retain an intimate connection with the other-than-human; and for whom material reality is, “maybe one hundred trillionth of all Creation, a tiny physical fraction embedded in a much larger relational web of spirit” (p. 218). For it is this estrangement that provides the measure of how much we have lost; and of how much we are still losing through the continuing loss of habitats and the extinction of entire species.

The quality of its prose and the logic underpinning its argument are, respectively, stylistically well-polished and thoroughgoing; the choice and use of its various interlocutors a treasure chest of sources and ideas. As we have come to expect from Scarlet Imprint, the quality of editing, typography and book design meet the highest standards. The cover design, in particular, is simply stunning. I cannot recommend this work highly enough.

Language begins in poetry and ends in prose. It is a process of losing the life in it over time, and that today we have to strive to experience or convey that aliveness in language – through poetry for instance – where our ancestors did so effortlessly. Old languages did not ‘aim’ to convey aliveness, they just did. (p. 64f.)