‘A Book of Deviations’ by David S. Herreías

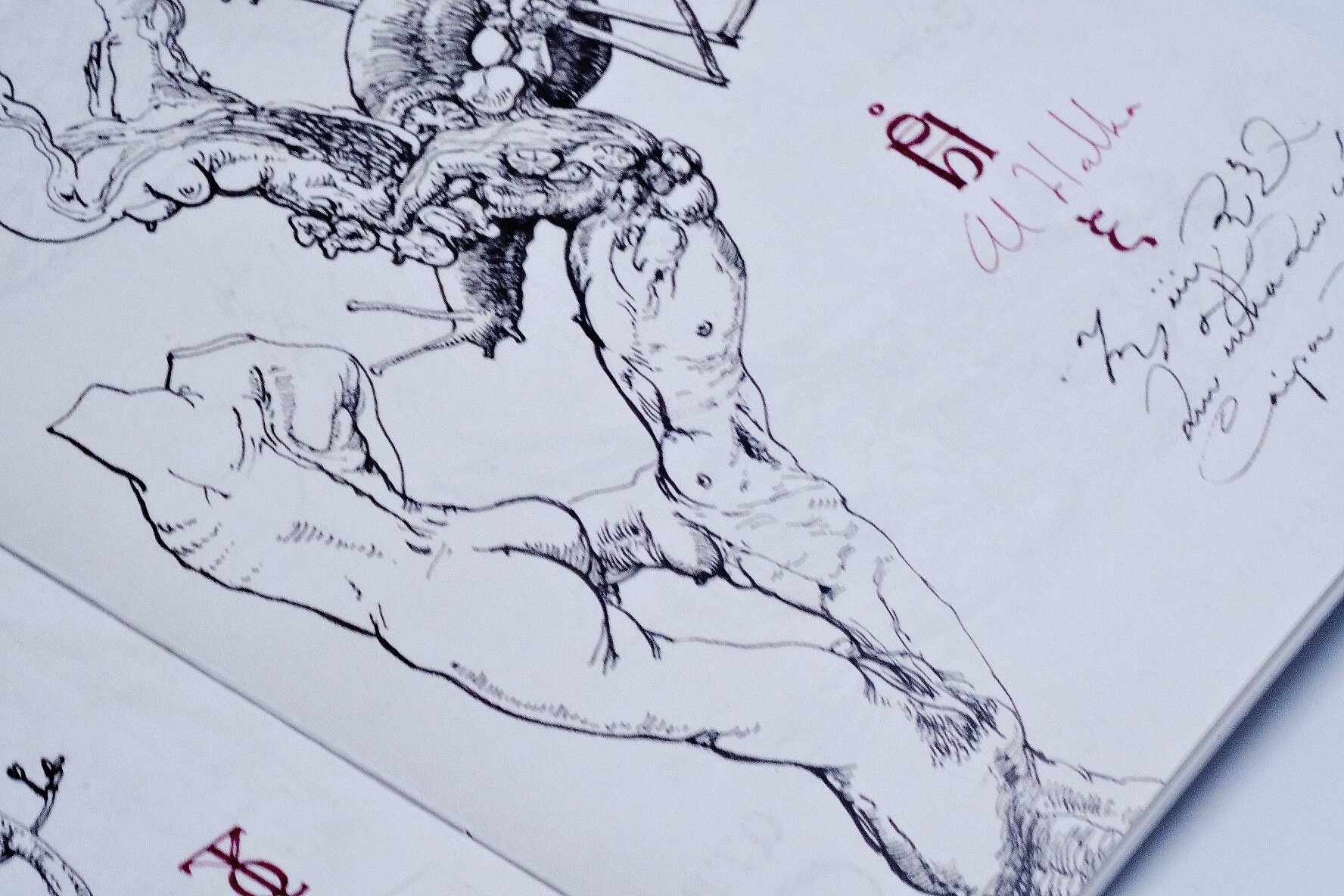

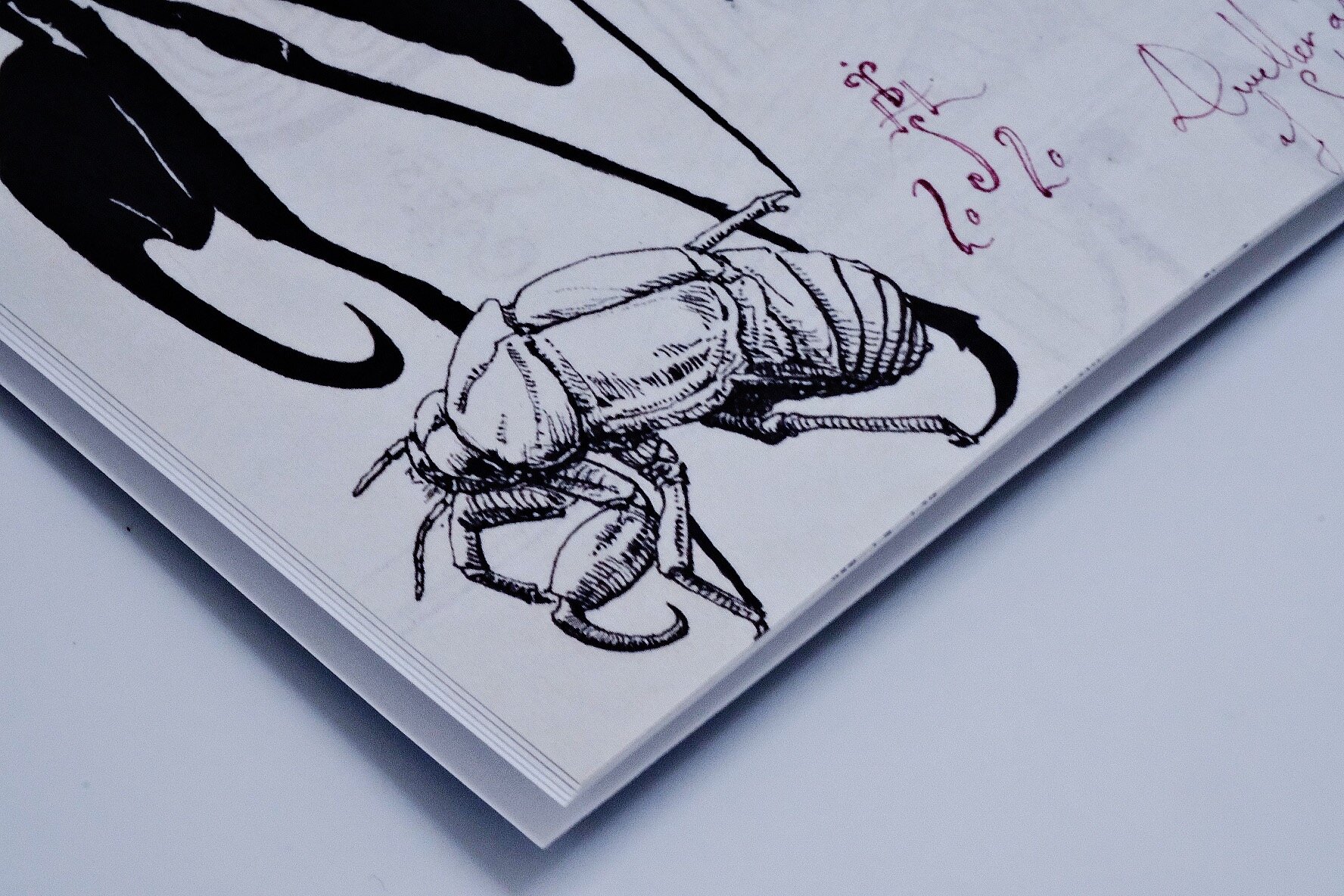

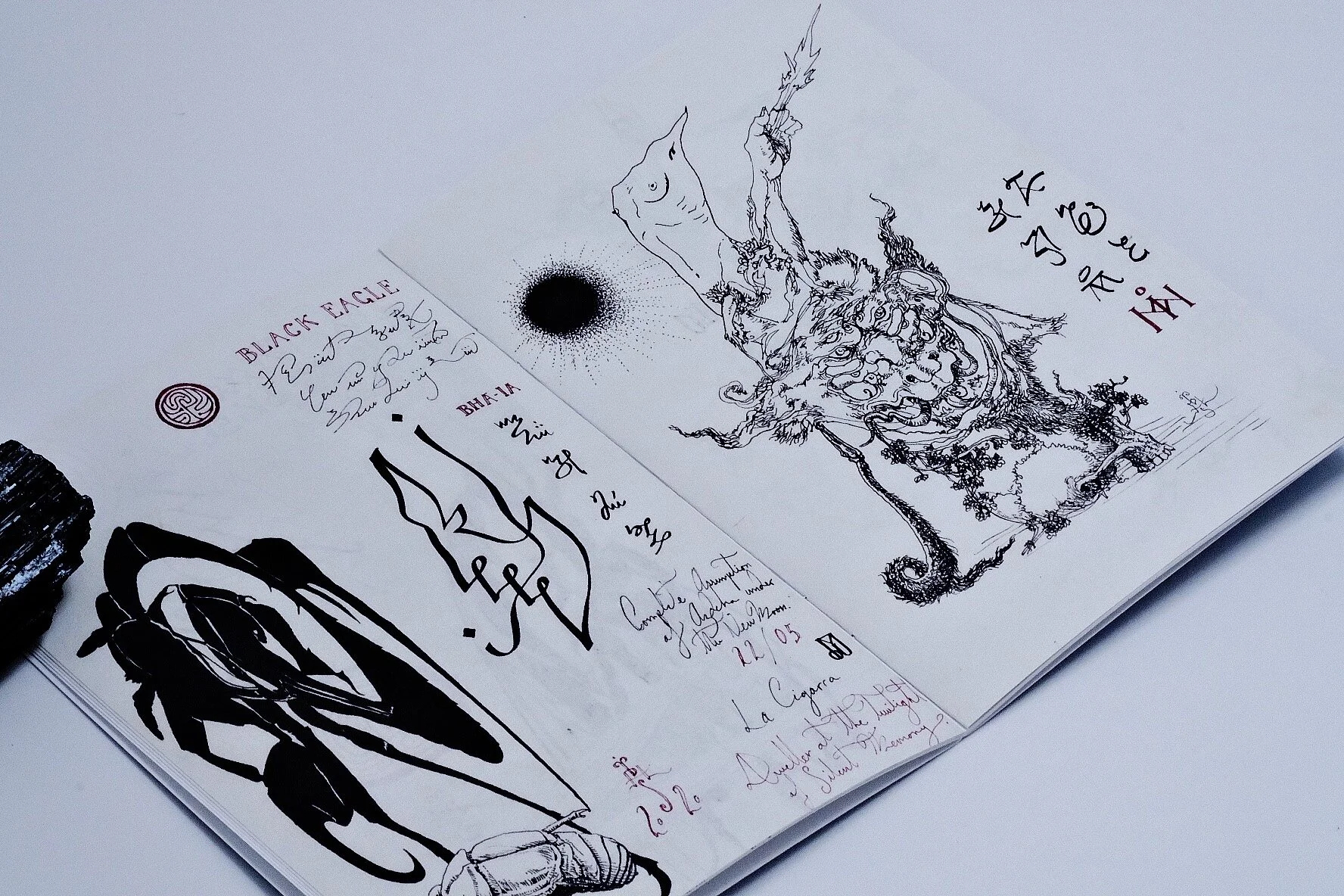

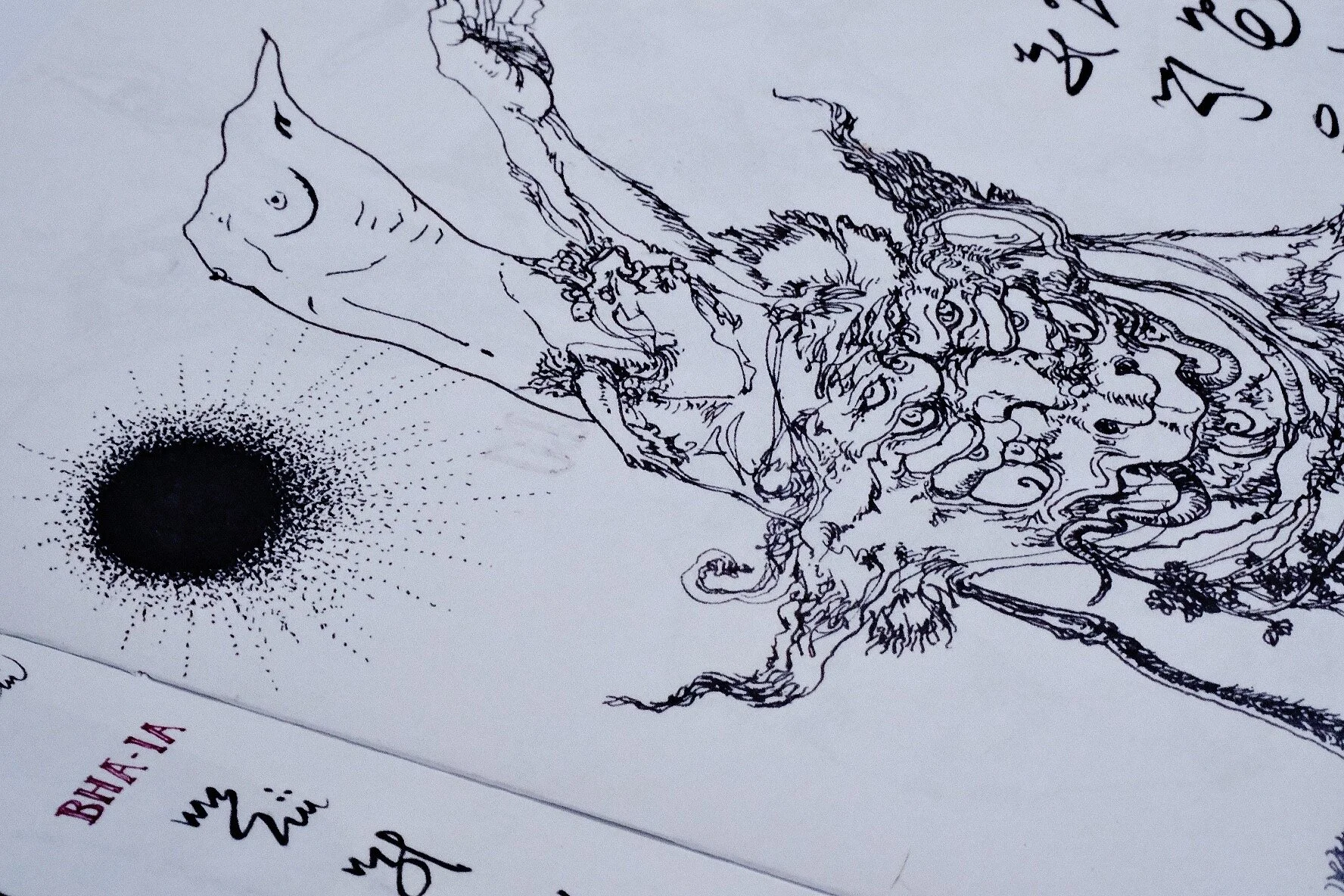

Review: David S. Herrerías, A Book of Deviations, s.l., s.d., published and distributed by the author, 2020, edition of 100 copies, 22 pages, including 7 original drawings in black, red, white

by Frater Acher

Over the last decade the work of Mexican born and Sweden based artist David S. Herrerías (DSH) has become a constant source of awe and inspiration for magicians and art-lovers within Western occulture. Notably his astounding 2019 release The Book of Q’ab-itz – still due for its own review here on Paralibrum – established his name not only as one of the leading artists within modern Western occulture, but also as a fearless lone practitioner of the art. In the introduction to The Book of Q’ab-itz, DSH shares some insights into the nature of his own path which masterfully dissolves the boundaries between acts of magic and artistic expressions. With a strong influence by authors such as “Grant, Spare, Bertiaux and Chumbley” (The Book of Q’ab-itz, p. 9), DSH is pursing his own kind of Crooked Path; one that meanders between the teachings of the people who walked before him – seemingly Andrew Chumbley and his Dragon Book of Essex in particular – and the direct teachings he received from the spirits he encountered along the path.

At Paralibrum we like to provide expert reviews; this means experts within the field of occulture will review books close to their own domain. Unfortunately, despite being a lone practitioner just like DSH, I am deeply unqualified to provide a review of a book whose practical foundations are inspired by the Dragons’ Column or the Sabbatic Alphabet. While I know there is much for me to learn from Chumbley’s writings in particular, I find them incredibly difficult to access: the desire to cloak simple things in obscure and seemingly arcane language just puts me off. This is why, despite my deep fascination for the visual seals and daemonic bestiary coming together on the pages of The Book of Q’ab-itz, I am not in a position to share a qualified opinion on it.

Now the above context is relevant to this review insofar that you can appreciate the delight I experienced when holding DSH’s most recent 2020 release in my hands: A Book of Deviations. This small pamphlet in many wonderful ways breaks away from the very patterns that made most previous releases of Crooked Path practitioners inaccessible to me. A Book of Deviations is a deliberately understated publication, short and concise, coming up to twenty-two pages only, saddle stitched and self-released by the author without any grandeur, but so low key that many of us might actually not yet have heard about it. Most importantly though, the instructions DSH gives on its thirteen pages of text shine with pristine clarity as well as practical relevance to any lone practitioner. This is a book for all of us; and especially I’d say it is a book for magicians who are engaged in Shadow Work, i.e. work relating to the Dweller on the Threshold and the Veil of Paroketh.

So what is the practice DSH invites us to explore in A Book of Deviations? Well, you might remember Frater U∴D∴’s review of Tsultrim Allione’s Feeding Your Demons which recently featured here on Paralibrum. If you are familiar with her Chöd-inspired classic practice, you hold a good foundation for the workings explored in A Book of Deviations. However, there are some essential differences in approach. Where Allione’s procedure emerges from within a context of Bön and Tibetan Buddhism, DSH’s technique is much more accessible to Western practitioners who are not familiar or tuned towards Buddhist language. Secondly, A Book of Deviations breaks the wall of remaining entirely confined to a meditative mental practice. In fact it revolves around the art of automatic drawing and thus offers a slightly more chthonic or goëtic approach to the work as the practitioner will make their demons flesh, at least on paper. Finally, by nature of its technique it is a practice especially appealing to artists.

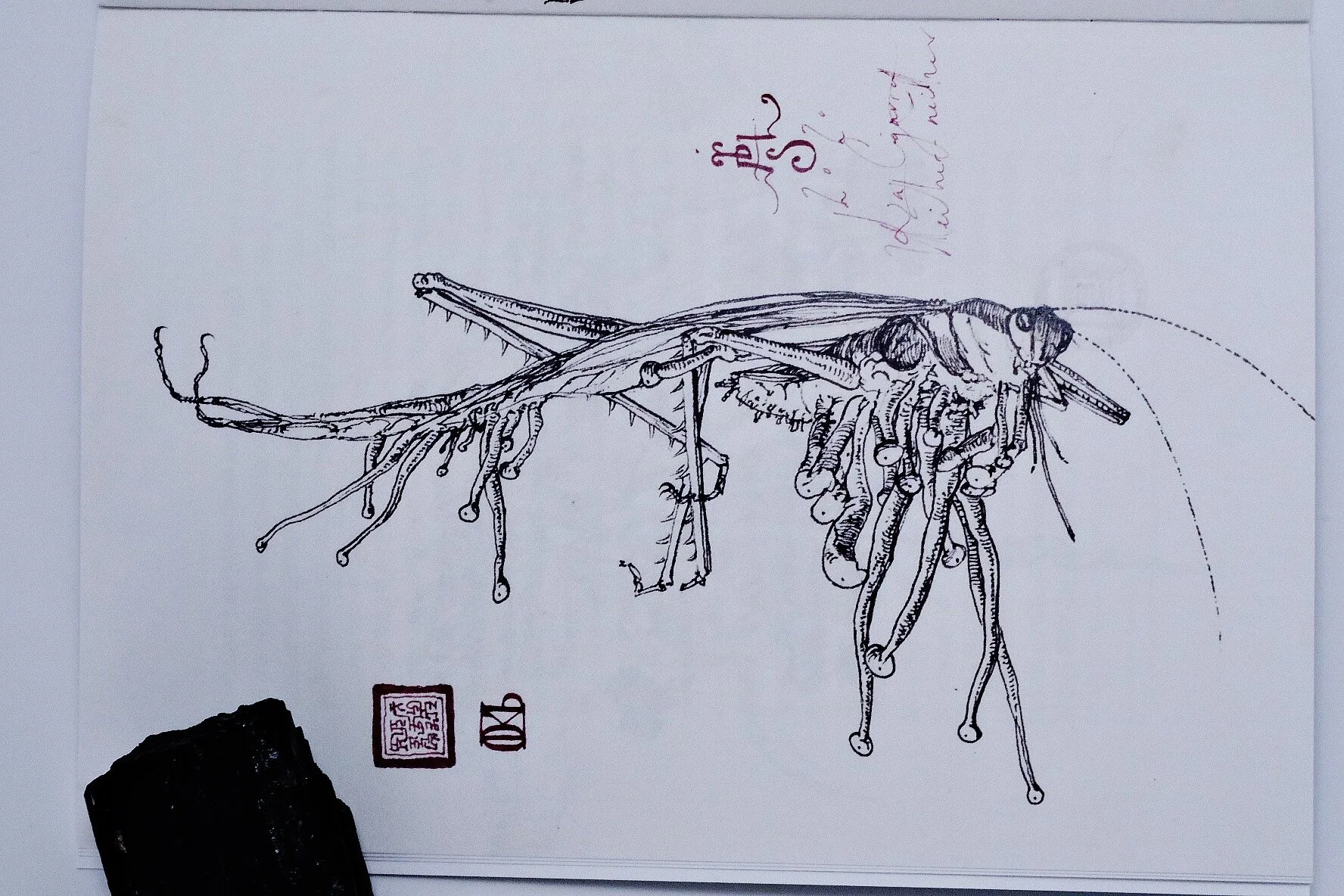

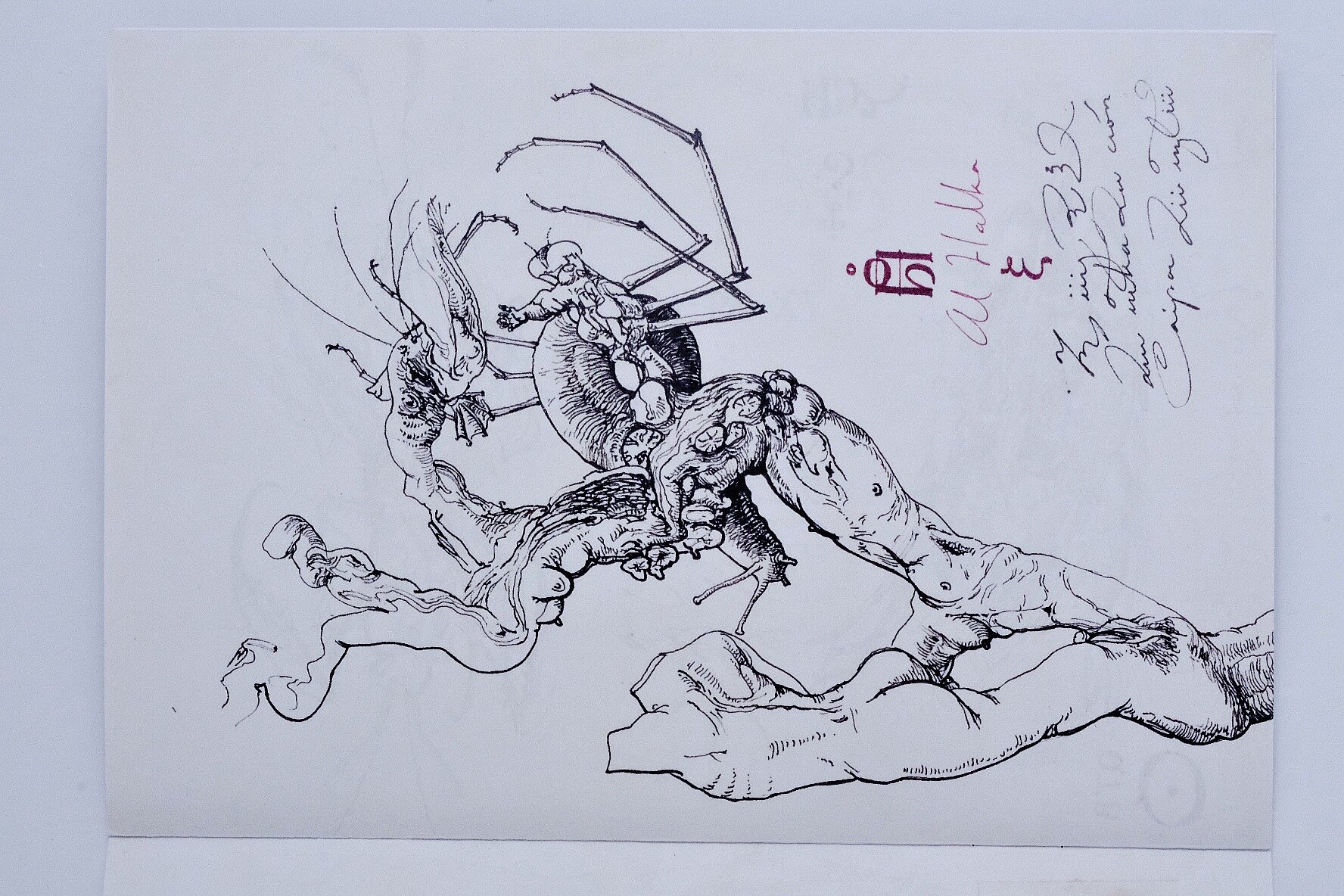

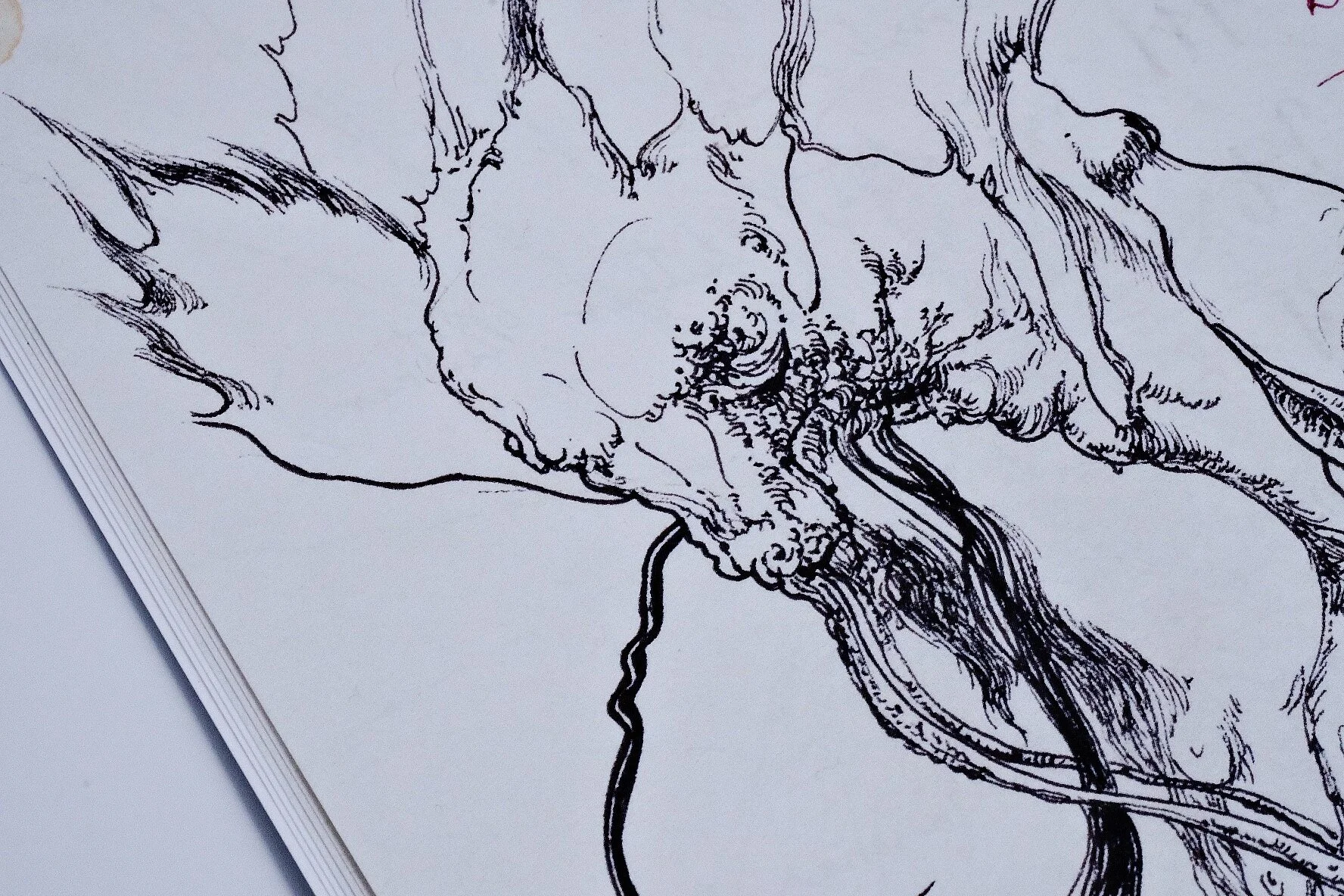

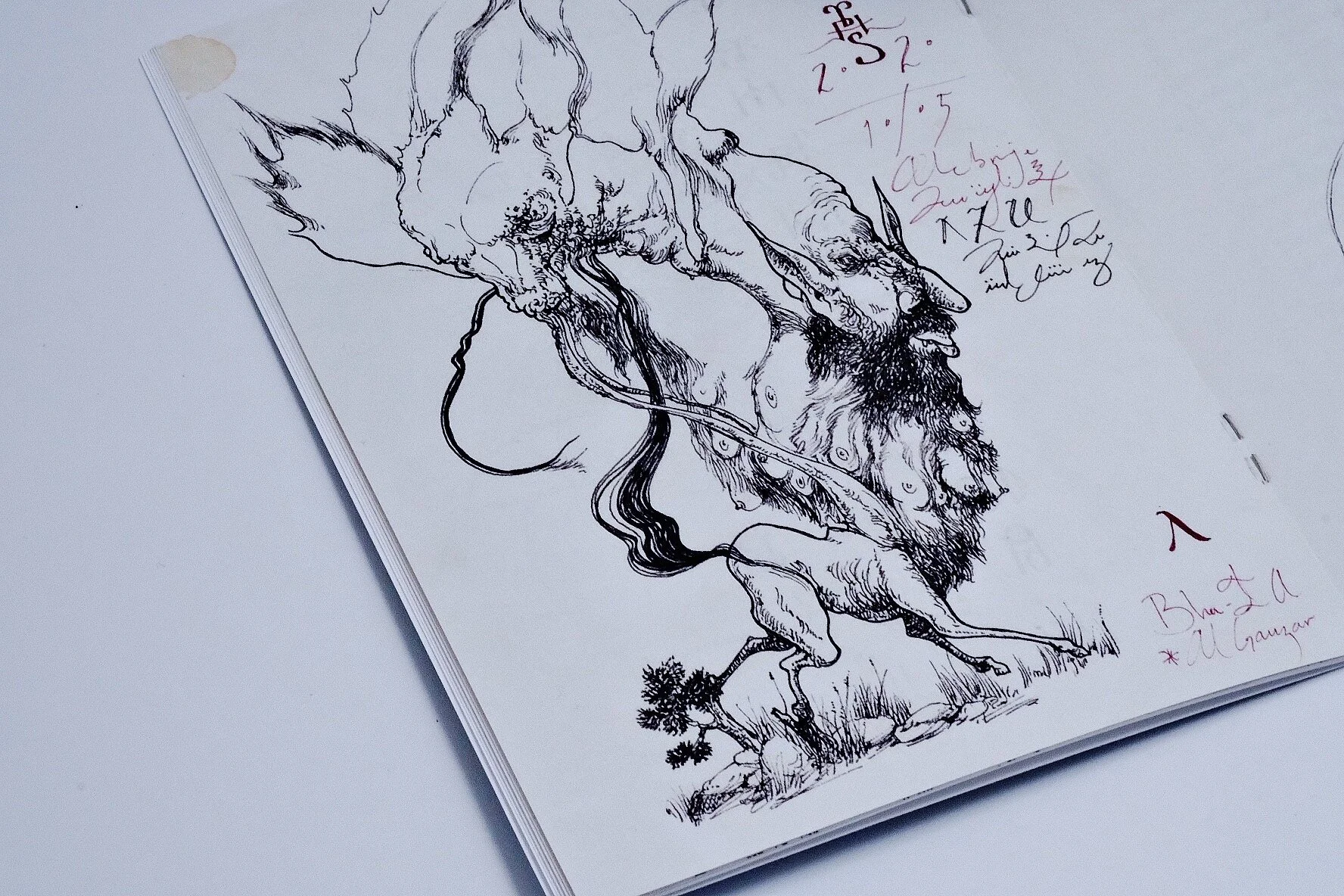

Having said this, from a magical perspective the quality of the automatic drawings produced during the work is irrelevant. These drawings are not a means to produce either beauty, terror or perfection in an aesthetic sense; rather they are a device to capture your demons in a physical form, just like you capture insects in a glass or spider web.

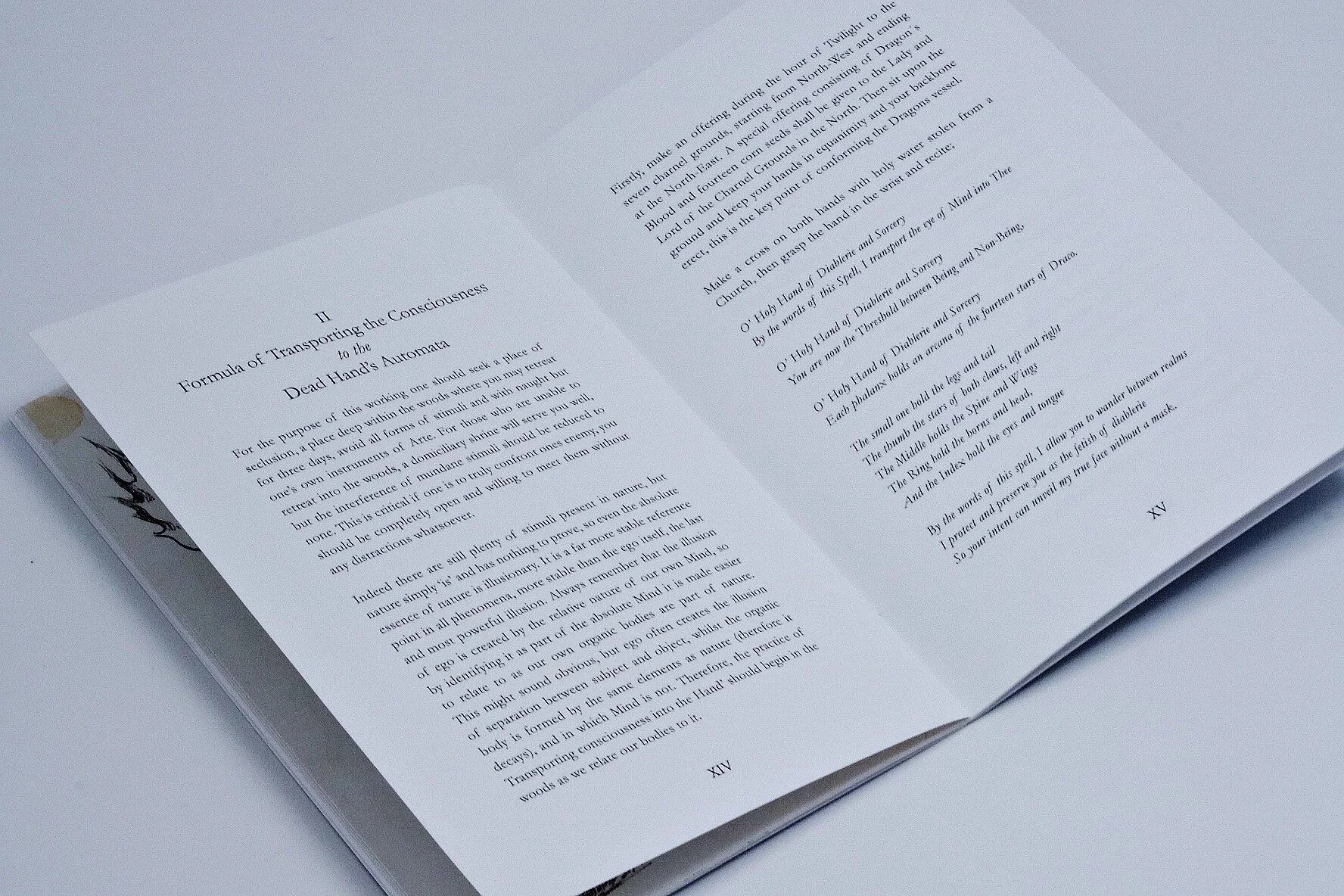

The process to engage in this work that DHS lays out for us is titled the Formula of Transporting the Consciousness to the Dead Hands Automata. The guidance begins with the classic instructions to find a remote place bar any distracting stimuli; ideally a forest at night. Performing this rite out in the wild seems particularly adequate as we shall see from the following. We are then asked to provide an offering to the “seven charnel grounds” (p. xv), yet it is not specified how the number 7 is applied to the circle. We have to presume DSH is referring to a practice familiar to members of the Cultus Sabbatai; most likely what is meant are offerings to the four cardinal points, above, below and the centre. Next, we baptise our hands as the essential paraphernalia of this rite and go on to “grasp the hand in the wrist and recite” (ibid.) a spell that is fixed upon our drawing hand. What follows is the actual access gate of the rite and an evolution of the traditional Chöd practice:

Keeping the eyes neither open nor closed and your vision directed inwards, visualise one’s own body as a corpse, for this is the key point of the Death Posture. Once this vision has been properly fixed within the mind, without any other mental fabrication whatsoever, one should proceed with the distillation of the five elements within ones [sic!] own lifeless body. (p. xvi)

DSH provides visualisations that transform our mortal remains from Earth into Water, into Fire, Air and finally Space. It is the description of these transitional stages that hold particular magical prowess in my eyes; for these stages are not to be merely imagined but to be experienced in vision. Practice as always trumps theory: sitting alone at night in a remote forest, no lights, holding tightly onto the beast of one’s invoked wrist, and seeing one’s decaying body shift forms, passing through the purifying gates of the elements and arriving in black nothingness… We are all architects of our own fate. And as magicians it is the courage to design and enter experiences like this that will alter our life’s path forever.

A dark-blue cloudless sky shall remain within your Mind. Rest within this vision and remain in this key point for as long as possible. Relax both body and Mind and allow the hand to move itself freely.

Some demons and spirits that remain hungry will arise at this stage in the form of thoughts to try and disturb your Mind, but transmit these into the hand so that they can be expressed and pierced on paper by means of dot and line.

If there is fear, jealousy, anger, sadness or joy, continue operating with these specific entities as long as possible until they have been pacified. Do not care about the talent of the expression, but rather the talent of operation of the rite. Recognise these drawings and sigils as an expression of your own demons that need to be fed and pacified. (p. xix)

The magician then sits in the middle of this stream of consciousness: the Void of open space and emptiness on one side, the familiars of one’s impure heart on the other. The former hanging above one’s head as a silent blue cloud, the latter pouring out from one’s heart through the conjured hand, being pinned in demon-shapes of ink and paper. – Finally, the spell is broken and the practitioner reclaims control over their body and hand:

In Space Shapes and Colors Form, but neither black nor white is tinged. With Words and Deeds this rite is done! O’ Holy Hand you are one with Space, and therefor [sic] now on my command! AMN (p. xx)

These ritual instructions form the final of three parts of the short pamphlet. In the first part DSH strikes a more philosophical tone and elaborates how this technique can be used to pierce through one’s “relative Mind, in order to realise its absolute nature by means of automatic drawing” (p. i). It is in the middle section though that we find the most personal material of the book. Here we are introduced to some of DSH’s own demons, pinned down as part of his own dark night retreat of which itself we see a photo on the back cover. It is this magical contextualisation of his images – highly reminiscent in tone and style of some of the best drawings of Austin Osman Spare – that reveal the dynamics of this rite even to the passive observer. The meandering stream of lines, wavering between beauty and obscenity, are the nightly expressions of a heart purifying itself. The forms released are the demons encapsulated within our blood and manifold aspects of being. By pouring them into a particular shape on paper, we enable ourselves to see them as the Other, and we halt being bound into one a single consciousness with them. By witnessing the forms of our familiar demons, we create awareness, we expand the conscious realm in which we can make conscious choices.

Anyone who has enjoyed or even practiced Alejandro Jodorowski’s liminal Psychomagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions 2010) will quickly fall in love with this rite. While DSH intersperses names of spiritual beings that we have to presume relate to the practice of the Cultus Sabbatai, the actual practice as summarised above is accessible to anyone. And this is the credit we should give to DSH in particular. In this small booklet he achieves to take an occult retreat from a particular tradition and strip it bare of any unnecessary dressings. While echoes of the Dragon’s Column remain, they do not hinder the uninitiated practitioner to throw all of themselves into this arcane experience. The praxis described is an invitation to all of us. It is an invitation to walk out into a night of courage, with nothing but a bag of paper and pen under our arm, and to conjure the demons to visible forms that otherwise haunt us invisibly. We will then stand, bound in awe and terror, in light of the myriad insect eyes, the donkey feet, the vulvas and lingams and black night stars that reveal themselves to us. And we will have to face the essential question that draws a line between the witch and the mystic – do we throw ourselves into the Sabbatic dance, or do we sit in silence under a cloud of blue? Do we pursue the crooked or the straight path? What is it going to be for us, sitting in the night, surrounded by the forms of our familiars?

We hope this release – not despite but, rather, because of its intended understatement – will work as an inspiration for many. A practical inspiration for their own experiments, as well as a pragmatic inspiration on how to choose new and more nimble ways of publishing their material. The older ones amongst us still hold dear memories of the 1980’s culture of self-printed underground magazines. In a world of Instagram and social media, where everything is supposedly meant to reach everyone instantly, the Book of Deviations holds a particular power and charm. For it deliberately chooses the opposite path and, just like DSH’s visual demons, it has become visible only to the ones it was drawn to. Not controlling the distribution process of material too tightly, yet not pushing for mass market availability, opens a liminal space, a space where magic can take control and manifest.

Personally, I am grateful to Daniel Yates who pointed me to this highly recommended release and to DSH himself who sent me one of his final copies. Maybe instead of asking for another print round, it is time now to circulate the existing copies amongst us? Mine is already packed up, ready to ship to a magical friend, and to lead him out into the woods.